Ulrike and Jim Anderson presenting at the 2024 Schoeps Mikro Forum

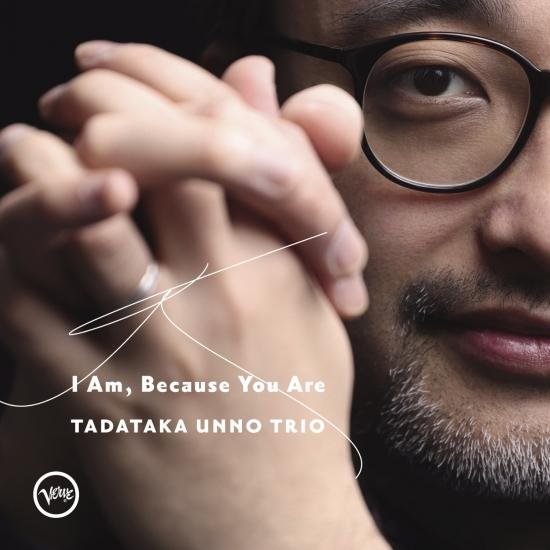

Tadataka Unno, “I Am, Because You Are” Review

Resilience in Harmony: Tadataka Unno’s I Am, Because You Are – A Triumph of Musical Resurgence

by Jeff Becker

Tokyo-born and New York-bred pianist Tadataka Unno is back with his latest album, I Am, Because You Are, an exploration of jazz that resonates with his journey, experience, and profound sense of being. Born to music-loving parents, Unno began his odyssey with the piano at a tender age of 4, seguing into jazz at age 9, ultimately leading him to graduate from Tokyo University for Music and Fine Art, a journey that propelled him into the limelight and a vibrant career, first in Japan and subsequently in the United States. Having shared the stage with notable jazz maestros at renowned venues and playing in some of the most respected ensembles, his music captures an aura of sophistication and an electrifying creative dynamism, reflective of his extraordinary career.

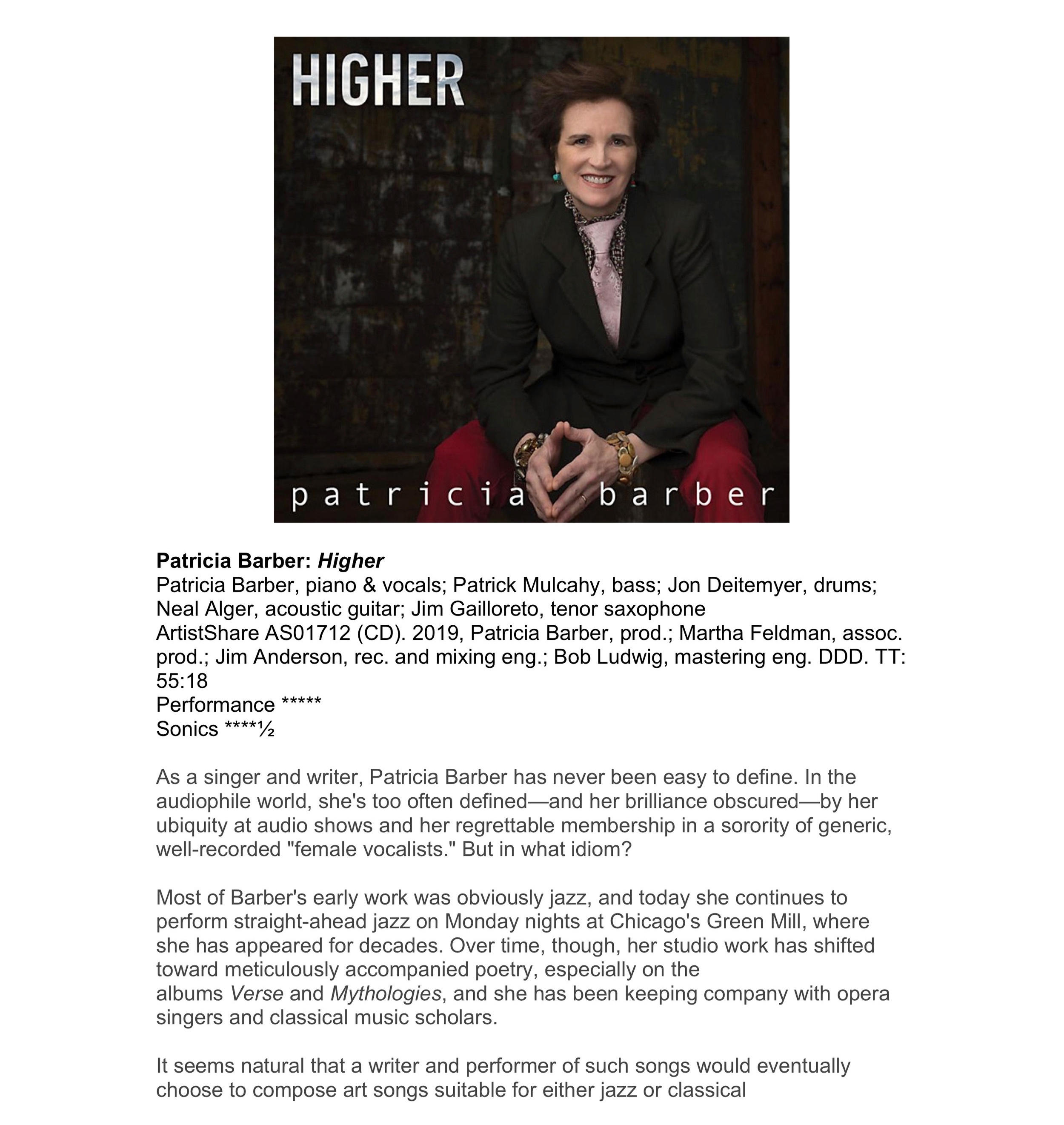

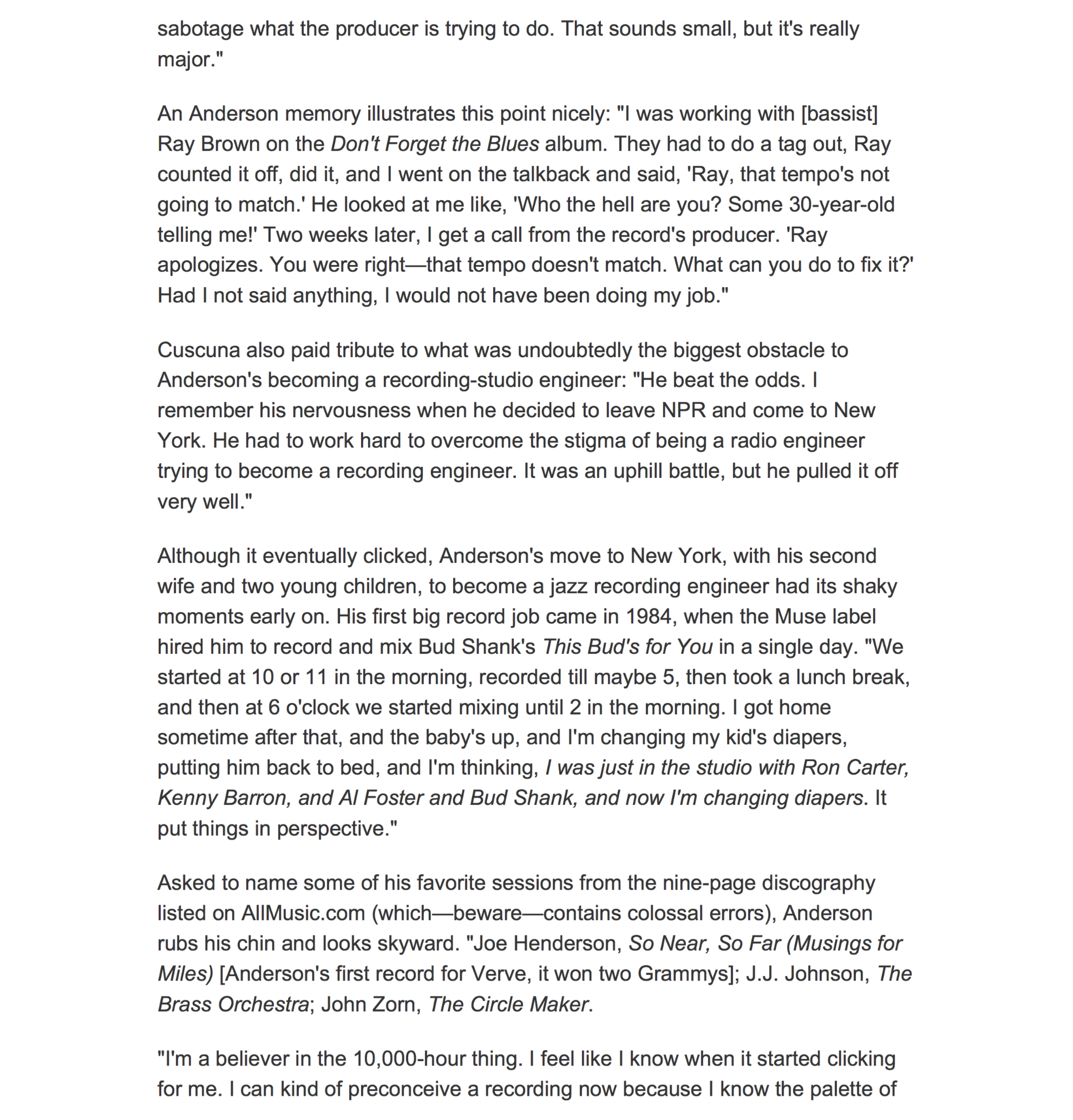

I Am, Because You Are is Unno’s second post-trauma album, coming to life after he suffered a horrifying hate crime in 2020. His triumphant return to music, his indomitable spirit, and his continued journey as a musician is elegantly encapsulated in this album. Recorded with regular collaborators Danton Bohrer on double bass and Jerome Jennings on drums, this all-original set is built around their deep relationship of trust and their understanding of the profound power of music in bringing people together. Recorded at the historic Van Gelder Studios in New Jersey, with mixing by the Grammy-winning engineer Jim Anderson, I Am, Because You Are harnesses the energy of the trio’s live performance, the intimacy of their connection, and the power of resilience, forming a compelling narrative that bridges personal history and the universal language of jazz.

The album begins with an elegant blend of traditional jazz and contemporary nuances, with a composition showcasing Unno’s consummate musicianship and emotional resonance with “Somewhere Before.” The trio’s skillful interplay is immediately apparent and is captured with an auditory experience akin to being seated in a college auditorium, immersed in the ebb and flow of a live performance. The reverberant drums, particularly the snare, create a spacious, atmospheric soundscape. Unno’s piano, melodious and flowing, takes the leading role, underpinned by the rhythmic constancy of Boller’s double bass.

“Cedar’s Rainbow” is another standout track. The piece commences with a tender solo piano rendition of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, serving as an emotive preamble before the trio plunges into an up-tempo composition. Seamlessly transitioning between straight and swing eighths, Unno exhibits a rhythmic versatility that infuses the piece with vibrancy. His melodic intuition remains at the forefront, beautifully threading together complex rhythmic patterns and engaging the listener throughout.

The arrangement of the instruments in the audio landscape — piano, drums, and bass — adds an additional layer of interest to the listening experience. Each instrument holds its unique space, yet together they create a harmonious soundscape, much like a well-orchestrated play on a three-tiered stage.

It is the balance of technical mastery, nuanced compositions, and emotional depth that makes I Am, Because You Are a successful recording of Unno’s talent. In conclusion, it is his ability to convey complex emotions through his fluid piano lines while communicating with his bandmates that is the heart of this album, creating a narrative that speaks of resilience, hope, and the joy of music.

“As I Travel” by Donald Vega Grammy Nominated for Best Latin Jazz Album, 2025.

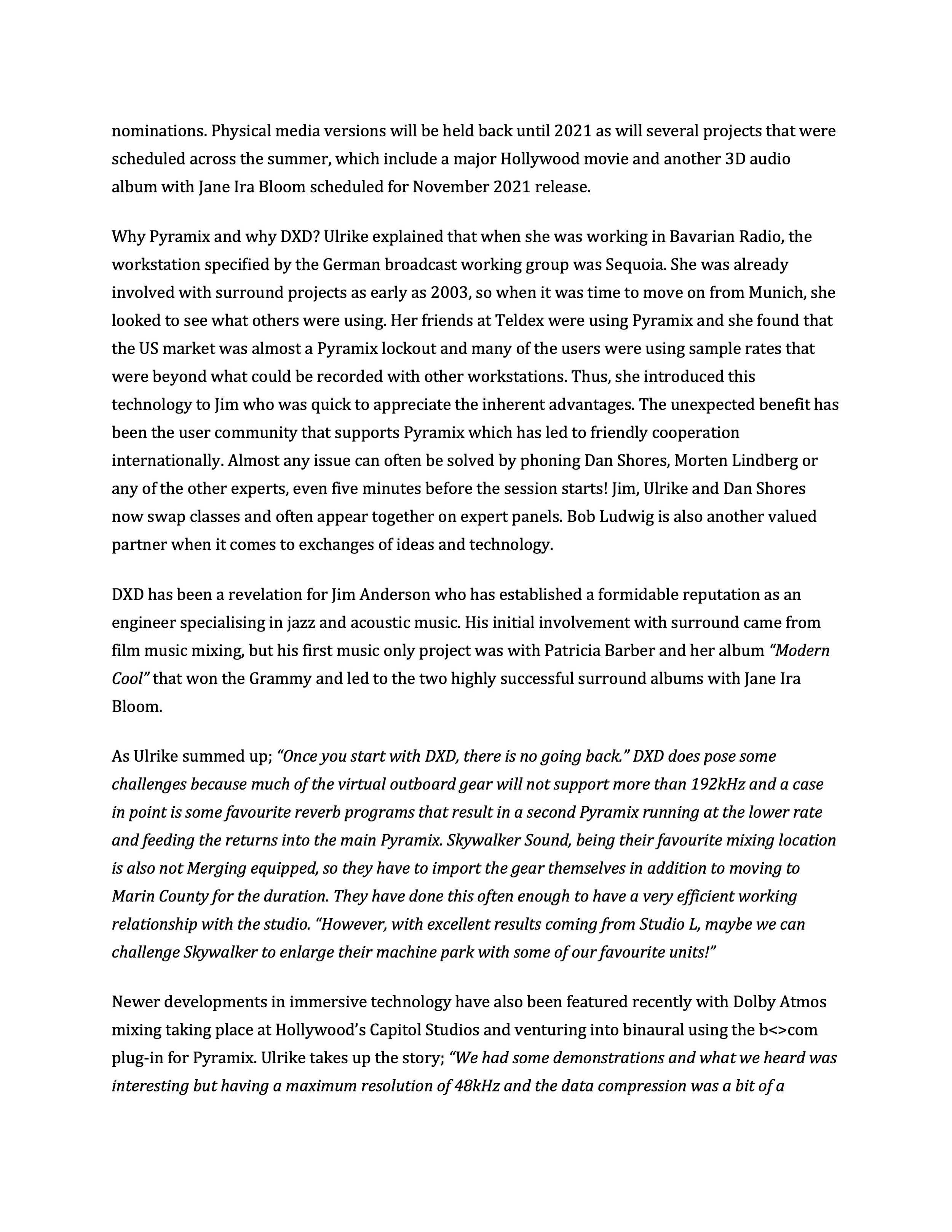

Patricia Barber’s 2022 GRAMMY NOMINATED ALBUM “Clique!” available on CD, SACD, Stereo and 5.1 Surround Sound and High Resolution Download and all streaming services.

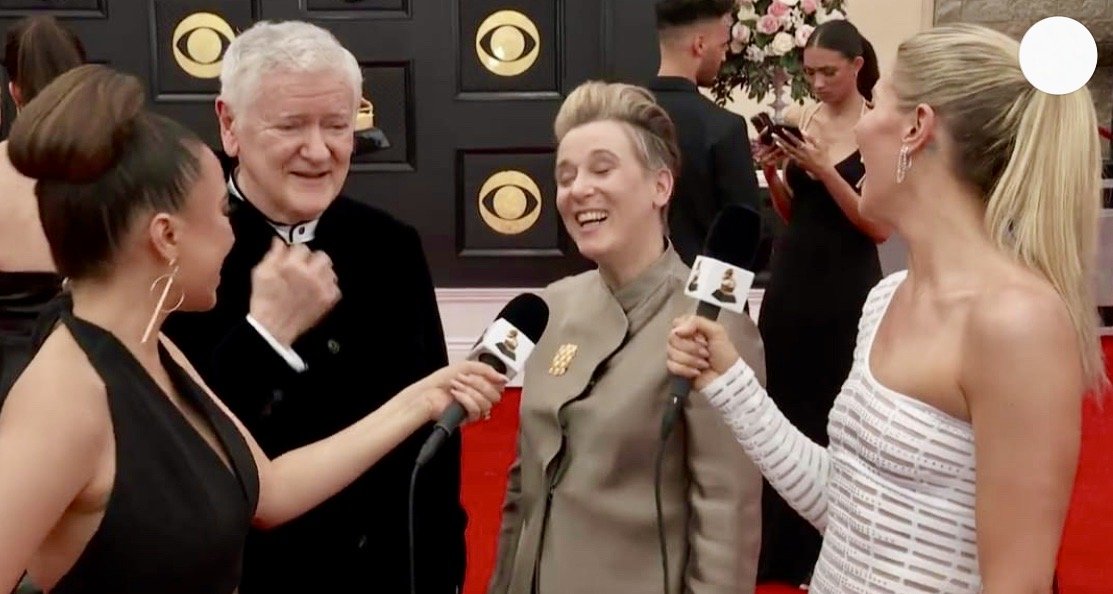

Ulrike Schwarz and Jim Anderson on the Grammys Red Carpet, Las Vegas 2022

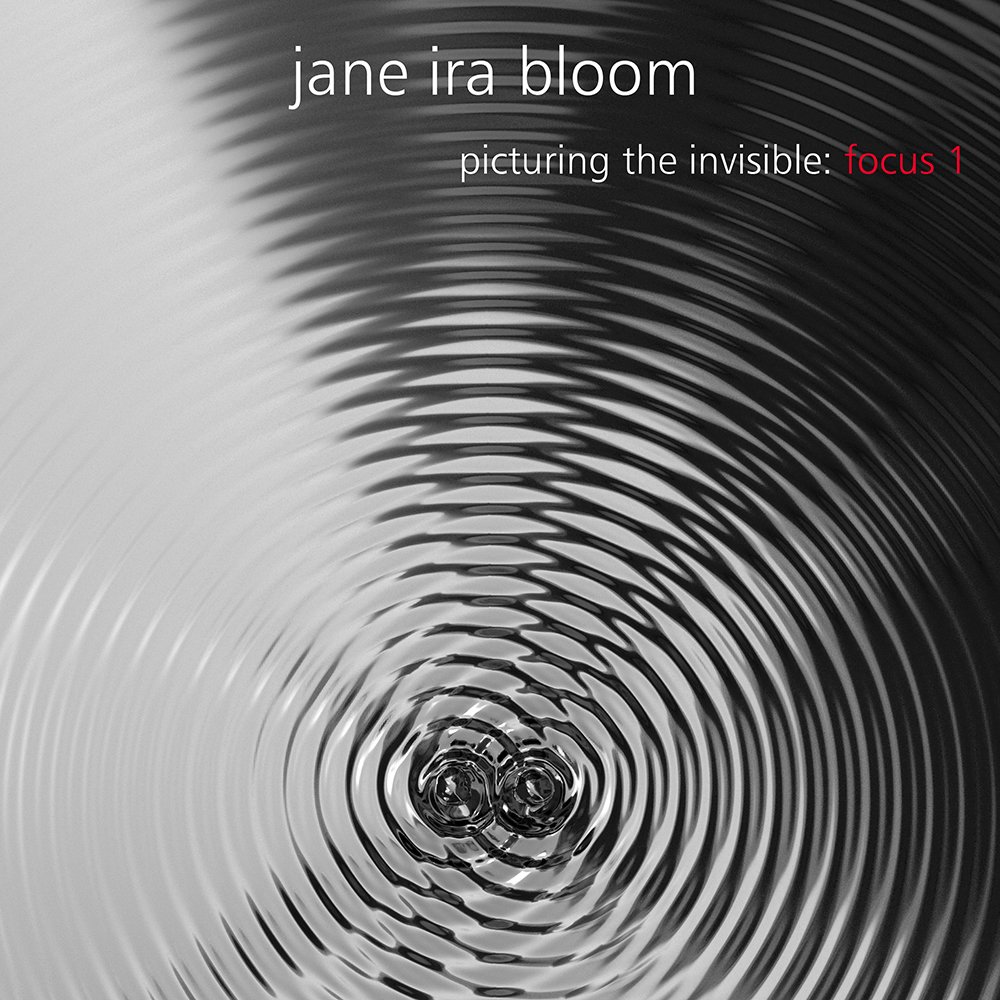

To read the full article, click here: Picturing the Invisible Part One

Click here for Part Two Recording Picturing the Invisible: Focus 1

”Picturing the Invisible: focus 1” Grammy nominated album (2023) available from Native DSD.

“For Best Immersive Audio Album, the nominees are…”

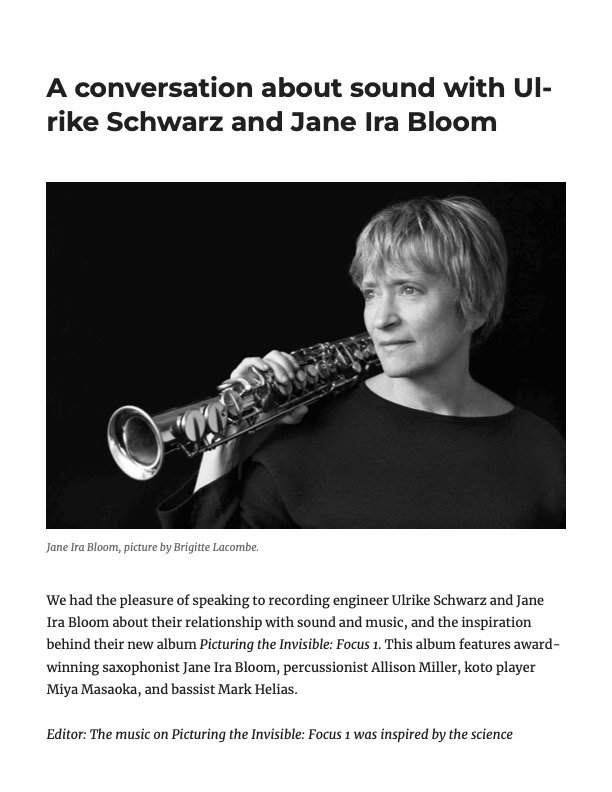

Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz: Immersive Audio’s Power Couple, Part One

Written by John Seetoo

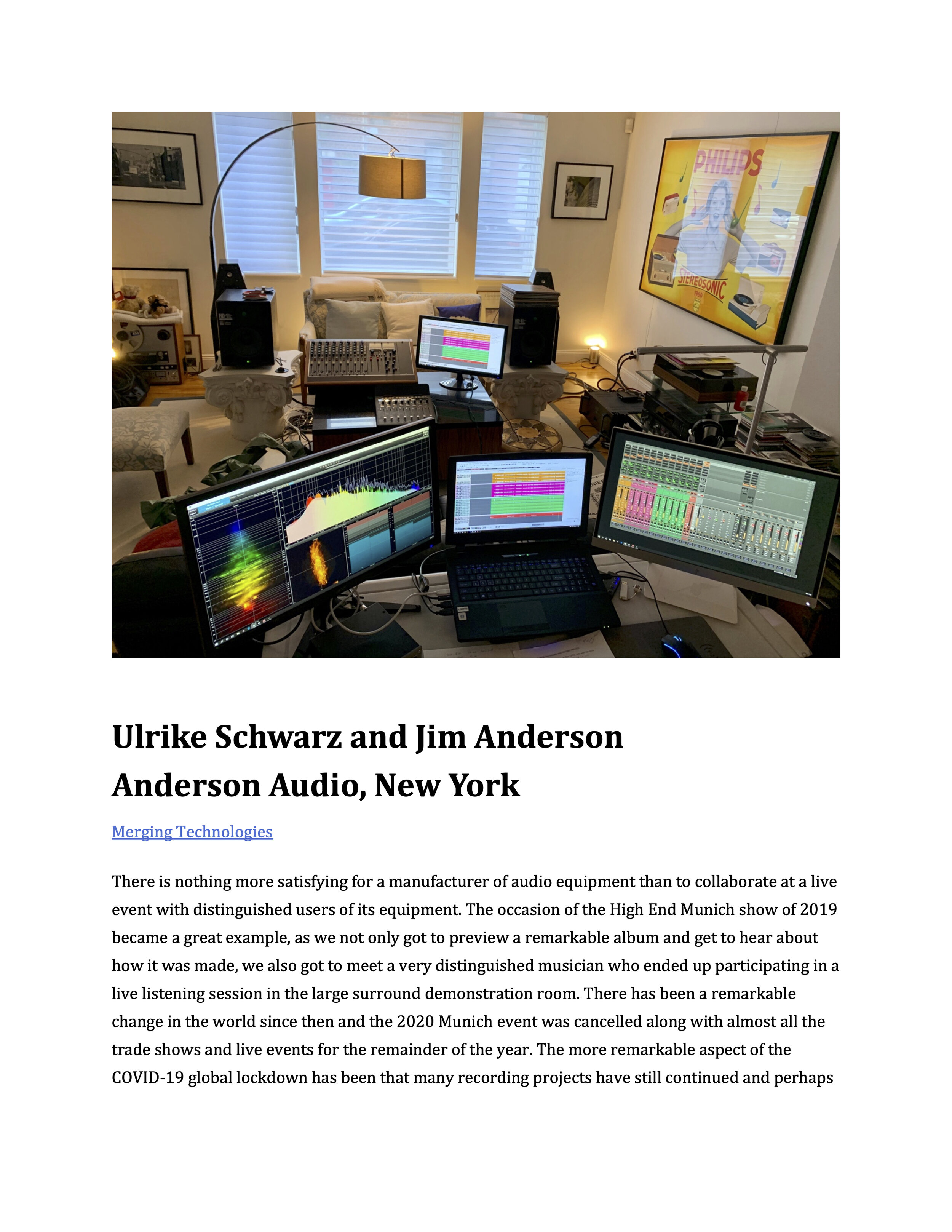

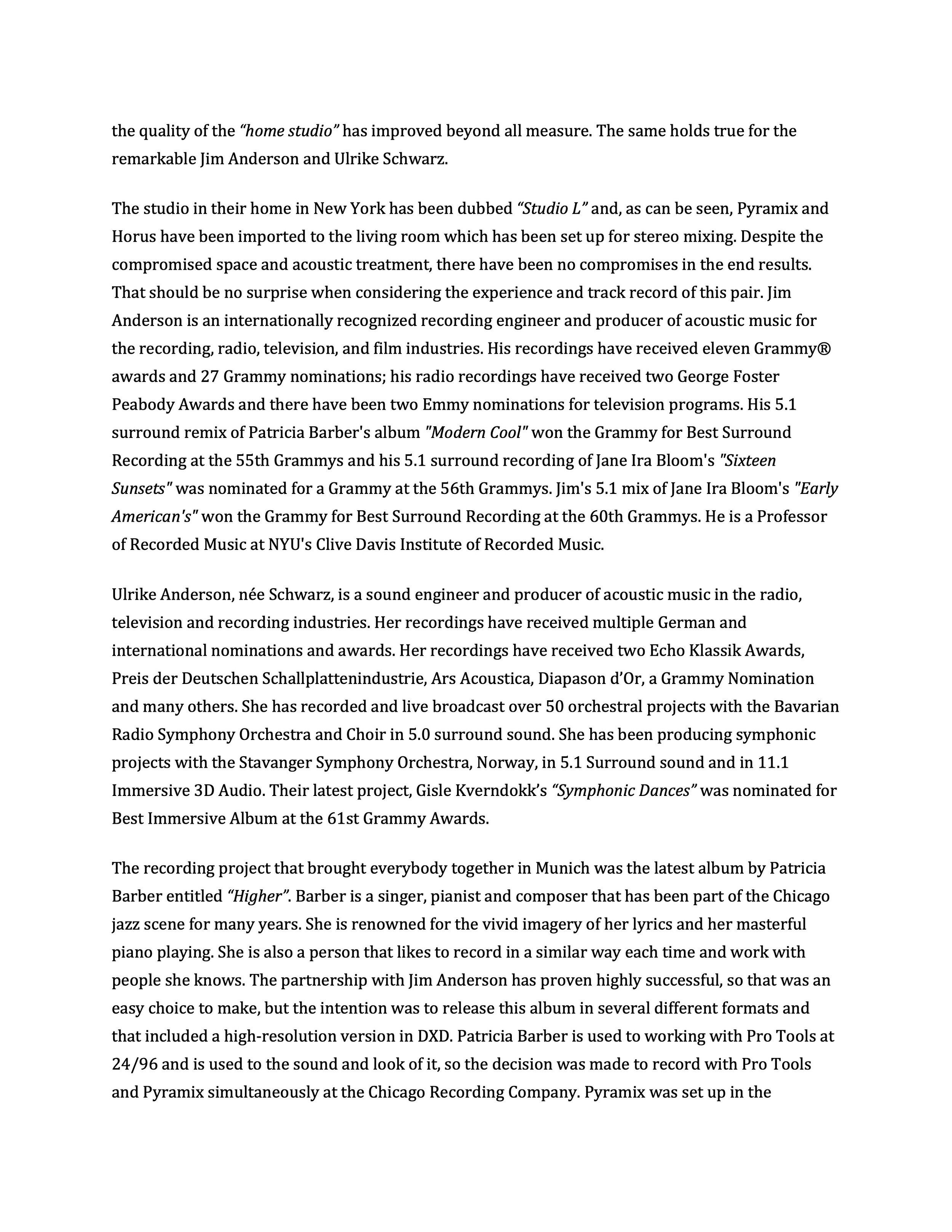

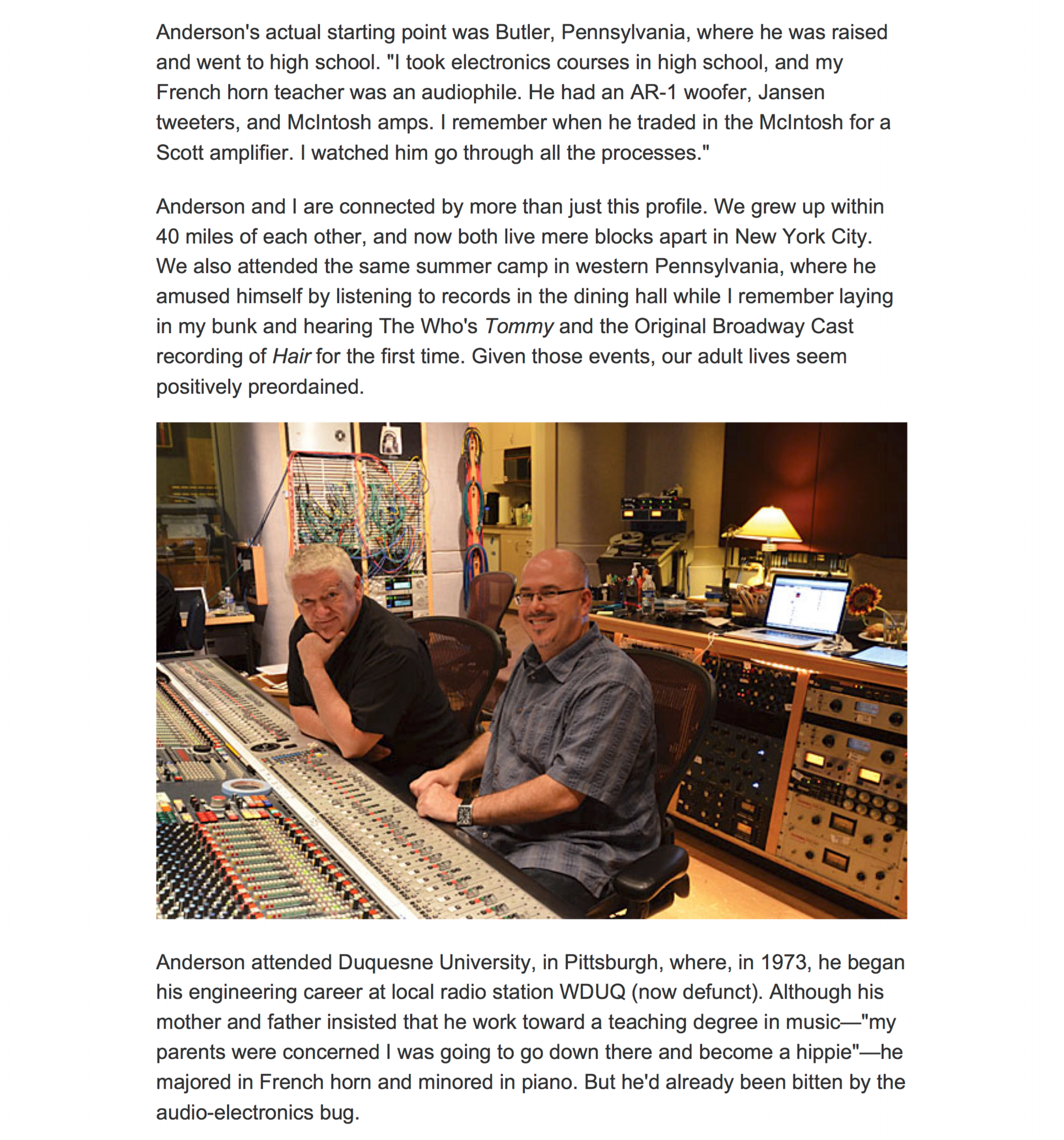

Married couples who work in the same field can often find that their relationship contains elements of both collaboration and competition. In the rarefied realm of immersive audio production, the technical skills and artistry required to sustain a reputation for unparalleled excellence are indeed rare. With multiple Grammy Award wins and nominations, as well as garnering European awards such as the Echo Klassik and Le Diamant d’Opera, Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz have created a unique partnership that has resulted in a wide range of critically-acclaimed co-produced and co-engineered recordings. Currently, they have a 2021 Best Immersive Recording Grammy nomination for jazz artist Patricia Barber’s Clique (reviewed by Tom Gibbs in Issue 144).

Jim and Ulrike graciously took some time to speak with us about their production approaches, techniques and philosophies, shared some anecdotes on the art of music recording and mixing, and elaborated on the particular challenges they have encountered for working in immersive audio.

John Seetoo: In a previous interview I’d read, you both went into a lot of detail about some of the special skill sets of professional recording engineers. Yet you also mentioned that the engineer’s work should ultimately be transparent or invisible to the listener, so that he or she should be able to just enjoy the music. Can either or both of you cite some examples on where this aspiration has been successful in your past recordings, and which ones in which you think the engineering aspect made itself a little too noticeable?

Ulrike Schwarz: I think I can start on the first part of the question, which means I think we can take Clique as actually a very good example. Because the idea is that you understand every word that Patricia says, but that it comes over as totally natural, and [as] if we hadn’t done anything [in the engineering]. However, Jim had ridden the fader on her voice, almost on every word.

[The album] sounds like all of [it] happens this way, which it kind of did, because it was a one-take recording. However, [the sound you hear] doesn’t come naturally, because, for example, your ending of words usually falls off in volume and stuff like that. [But] the impression you have is like she’s sitting on top; you can understand every syllable. And that’s the way it’s supposed to be.

Jim Anderson: We don’t mean to just put this on Patricia; this is really for every singer you work with, in that you really have to ride the fader, stay with them, and keep the voice really above [the rest of the mix] and all that kind of thing. It’s a very natural thing [for a singer] to let the voice trail off at the end of a phrase. But in a recording, you really have to counteract that; you have to kind of flatten it out. Now, you could do it with a compressor, people do it all the time – or with limiters. [Compressors and limiters are used to “even out” a signal’s dynamic range – JS.] But we would much rather have it be a more natural occurrence, rather than “kind of” fix it technically.

US: And the other thing is, of course, you hear solos, you hear bass, you hear the drum kit, and if everything was unmixed, basically the same volume all the time, it would be a big chaos. What happens is the engineer or the engineer and producer [essentially] arrange the music for you. When the bass solo comes up, the bass is getting louder. But the idea is so that you don’t have the idea it’s getting loud. This is the thing – it always has to be natural.

I can speak more to classical recordings, where basically the engineer and the producer interpret the score for you. If there is a flute solo, you have to give the flute a little bit of a push, otherwise it doesn’t come through. You point the listener into the direction that they should go.

JA: It’s like putting a spotlight on something or someone.

US: A subtle spotlight.

JA: Yeah, that’s the kind of thing we do, but you shouldn’t be realizing that that’s what we’re doing.

US: That this is what happened. Yes.

JA: There are techniques in how you raise the levels and drop them back. You develop them over the years about how to make them “transparent.”

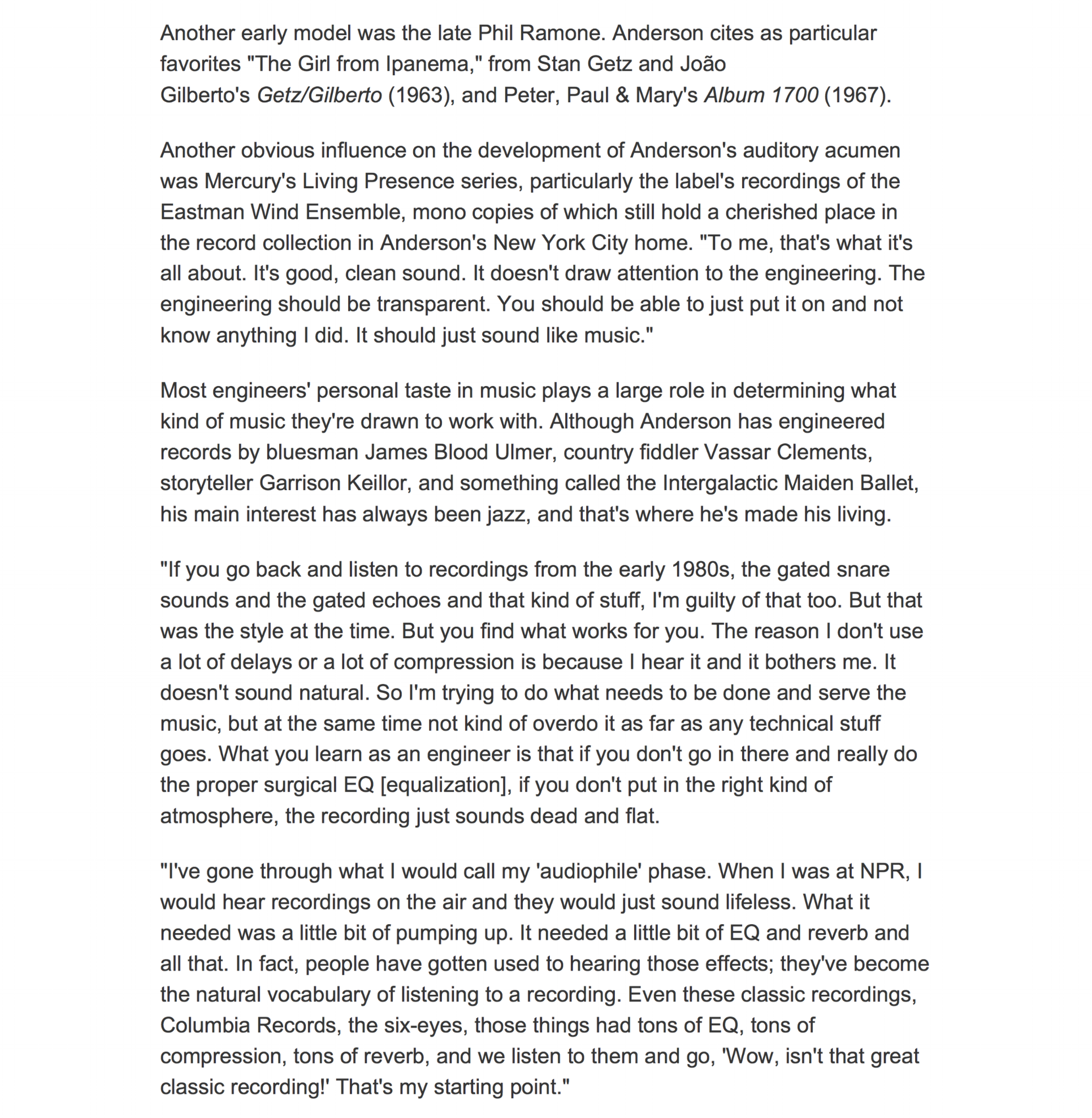

Jim Anderson

US: You’re not supposed to hear that somebody raised [the level by] 15 dB or 2 dB or something; you just notice, “oh, the bass is in the right place” because Patricia is always understandable, but you shouldn’t hear how that got to be done.

Another thing that was brought up in my studies is, if you are at a concert, and you look at a certain instrument, you always hear that instrument, but on a CD, you don’t have that information, all of the visual information is not given to you. And so, we kind of help it along a little bit.

JA: To [further] illustrate what Ulrike is saying: microphones are a very dumb thing. Microphones just sit there and take in whatever is in front of them. And if you’re listening, your brain is acting as the mixer. Essentially, that’s really what she’s saying. Because you see something, you hear something, and you kind of say [to yourself], “oh, I should be paying attention to that.” But microphones don’t do that. You have to be the brains behind the microphones, really.

JS: Which recordings would you say are good examples of where you’ve been the most satisfied with achieving this idea of your work being invisible to the listener?

JA: (laughs) Usually, it’s the last one you did; the latest one.

JS: So, it would be Clique?

JA: It would be. We would certainly reference back to it.

Sometimes you go back and you have some distance; you look back and say, you know, I would have tweaked this here, tweaked that there… Also, [once] you get a little bit of distance on a recording, you forget all the…everything it took to get the recording finished. And then finally you can kind of look back at it and address it honestly, [and] can listen to it the way other people are listening to it.

Because for a long time [after finishing an album], everything you did is kind of etched in your brain. And you can’t forget that for a long time. Sometimes it takes a decade or two to really go back and listen to a recording that you did, and forget what it took to get there via being in the studio or mixing or whatever. I think critics and listeners are the ones who will tell us if we’ve been successful.

US: I wouldn’t want to take down any project we’ve done for clients by saying, “oh, you know what, we didn’t really do such a great job.” That’s something I would rather not answer. (laughs)

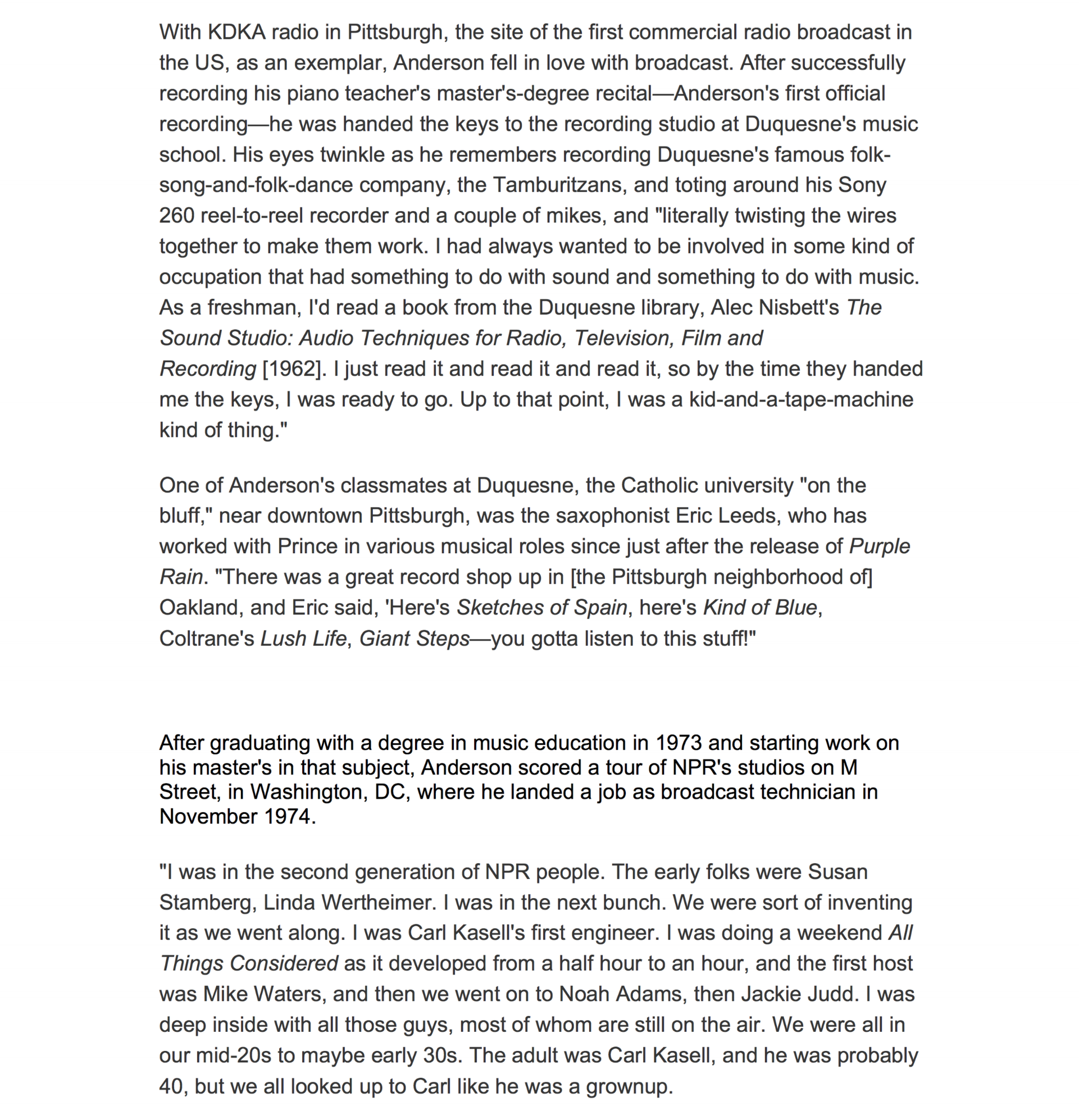

Ulrike Schwarz

JS: You both have decades of experience in recording everything from small ensembles up to full orchestras. Do you have designated specialty areas when you work together, where say, one of you gets better results on drums and timpani, or the other gets better piano or woodwind sounds? This also apply to mixing: do either of you have sweet spots where one is perhaps better with recording vocals and the other is better with piano or other elements?

JA: Well, if I can speak for Ulrike…her orchestral work, I think, is really quite good. She specialized in that for 15 years and was doing it live in stereo and surround on a weekly basis. When you work under that kind of pressure and that kind of timeline, you get to be pretty good.

I used to go and do a jazz festival up in Detroit every Labor Day weekend for about 20 years, doing live mixing for national public radio broadcast of 40 bands over the course of the four days and I would do it just [to] keep my chops sharp. One hour it’s a big band. Next hour, it’s a trio. The next hour…and it will [keep] changing. It’s a really good experience and good practice to do that kind of thing.

US: I’ve grown up in the hall in the classical world. [In learning how to record and mix], they start you off with chamber music, and then [you] get to orchestras. My favorite thing to do was, the bigger the better. At some point, it was like, a 90-to-150-piece orchestra with 80-to-100-person choir. That’s when I thought, “okay, this is fun.”

My overwhelming body of work would be in classical music. Not all of it is released; most of it was for national broadcasts, or broadcasts in Germany and Europe.

I have done quite a bit of jazz, and even rock, which are the things that also come along, of course, at a [broadcast] network, but probably what I would think my specialty is, is really large-ensemble classical music.

What else I really like to do is folk music, that kind of German Alpine folk music, because [growing up], it was part of our DNA. And I’ve learned [about] folk music [in other countries] when I traveled. I spent a fair amount of time in Japan, and when you know how people want their folk music to be recorded and to sound, then you kind of know how they want all their other stuff to sound like too, because I’ve noticed that the approach to classical music in Japan is a little bit different than let’s say, in Europe.

I found out more about that when I spent a lot of time [in Japan] recording traditional Japanese music. And I think the same goes for jazz. I mean, Americans have a different idea of how classical music should sound recorded than Europeans, and that has very much been influenced by how [they] listen to jazz, rock and roll, and all these other things. So, there’s a lot you can learn from the folk music of the continent or the country that you’re in, in terms of extrapolating it to other styles of music.

JS: Actually, that touches on a question I want to ask you a little later. Say you had to record a jazz big band, like the Toshiko Akiyoshi-Lew Tabackin band. Which one of you would be more prone to take the lead?

JA: (laughs) Probably me, only [because] I have a long history of association with Toshiko Akiyoshi and Lew Tabackin. I think I’ve done about 10 big band albums [with them], and probably 10 of Toshiko’s small groups. [We go] back almost 50 years, at this point. Also, I love recording big bands.

US: My favorite three recordings of Jim’s are all actually big band recordings. One of them is Joe Henderson’s Big Band. Then there is J.J. Johnson’s The Brass Orchestra and Ed Palermo’s The Ed Palermo Big Band Plays the Music of Frank Zappa. For Ed Palermo and Joe Henderson, I was actually one of the assistants, because I wanted to learn how to record a big band from a certain Jim Anderson, who was an engineer that I really admired a lot. So, there you go. (laughs)

JA: Yeah, and big bands are fun to work with. The other thing though, is – big bands, especially these days – you can’t cover them with a pair of mics and do it like you maybe would live. There was one big band that we did at Avery Fisher Hall in Lincoln Center for NPR with Woody Herman in the late ’70s. They were performing a piano concerto that Chick Corea had written and the fact was that I could actually take a stereo microphone and cover all 15 horns – with [just] a [single] stereo mic (an AKG C-24) – that was because that band played on the road 49 weeks a year. I think that was probably the most, let’s say, “audiophile” [big band recording I’ve done] in that it was very limited in the [amount of] microphones [used], and we were [recording it] at Avery Fisher Hall.

I had an AKG C-24 stereo mic over all the horns, a solo mic down front, a mic on the piano, a mic on the bass, and a mic on the drums. And that was it. It was like six microphones. And it [turned out to be] a really great live recording, and made for a great [live] broadcast. It was so simple.

But it was a band that had played; they knew how to make an ensemble sound. You get a big band in a studio these days, and they usually haven’t seen the music. [Bandleader and arranger] Bob Belden used to say, “it’s always take two or take three,” because the first take is a run through, the second one is maybe going to be OK, and then the third one is probably going to be the best. So generally, when you’re working with large ensembles like this in the studio, you get – maybe if you’re lucky – three chances to get it right. So, you have to be really on your game all the time.

JS: Ulrike named three favorites of your work, so what are your three favorite records of hers, where you said, “wow, I couldn’t have done any better than what she did.”

JA: She recorded a box [set] of Beethoven’s nine symphonies with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Mariss Jansons conducting. I could pull three of those symphonies out, the Fourth, Seventh and Ninth, from the Beethoven box, as my favorites, if that counts (laughs). I want to say that, to me, they’re the rock and roll of classical music. It has power, it has impact, and it’s just a really great set of recordings. [The sound is] not like it’s set back from the hall. You’re really, really inside the orchestra. To me, it’s the state-of-the-art of what you can do with modern recording techniques in recording classical music.

They were mixed from multitrack [recordings], but they’re not edited to death, mixed to death. They’re really spontaneous.

Link: Copper Magazine - Part 1

THE COPPER INTERVIEW

Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz: Immersive Audio’s Power Couple, Part Two

Written by John Seetoo

Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz have multiple Grammy Award wins and nominations to their credit, as well as European awards such as the Echo Klassik and Le Diamant d’Opera. The couple has a unique partnership that has resulted in a wide range of critically-acclaimed co-produced and co-engineered recordings. Currently, they are up for a 2021 Best Immersive Recording Grammy nomination for jazz artist Patricia Barber’s Clique (reviewed by Tom Gibbs in Issue 144).Part One of our interview in Copper Issue 156 included their thoughts on making their mixing techniques as “invisible” as possible, in working with live orchestras and big bands, and discussed their favorite recordings done by each other.

John Seetoo: When I was researching your discographies, obviously there’s tons and tons of classical and jazz stuff you’ve worked on, but I didn’t see that much for country, R&B, rock and roll and other kinds of music. Can you go a little bit more into some of the work you’ve done in those genres? Any particular anecdotes you might have? And, have you ever collaborated together working in genres other than jazz and classical?

Jim Anderson: We have a series of symphonic recordings that we’ve done with the Stavanger Symphony Orchestra in Norway. I was brought in as the engineer, and Ulrike as producer. She essentially was my boss for the three recordings, the last of which was a Grammy nominee two years ago in the Immersive [Audio] category.

And so, we had the chance to go to Norway; Stavanger, Norway, and work with an orchestra. The one nice thing that we were doing was [that] we were recording in sessions. We weren’t doing live recordings with patches [punching in passages in the mix] and things like that. We actually had an orchestra on the stage. We could put microphones down [on the stage in their best locations].

I think those recordings were very successful. [We had] a chance to go to a foreign country, bring in the equipment we needed, and actually have the time and the resources to do the recording [the way] we wanted to do [it]. They allowed us to [then] go out to Skywalker Sound and mix out there, and we mastered [the album] with Bob Ludwig. It was all first-class. So, I thought that was a really wonderful experience.

Ulrike Schwarz: Yeah, and about the mixing process: Of course, as somebody who has done orchestras a lot, having [the time and ability to do] a different mix – that was actually quite, quite interesting. The good thing is that Jim and I, we hear very much the same thing. We really know what we want in a sound, which is, I think, very, very important for a producer/engineer team: that you can express what you want to hear.

Because if you have two very different sonic ideas between a producer and an engineer, then you’re running a little bit into a problem. Then there is the third [problem] when the conductor comes in and voices another opinion. Because I think it’s very important that everybody’s on the same page. Otherwise, things get can get out of hand at some point. So, it’s something I enjoy very, very much – that [Jim and I] have the same ideas.

And it is very, very easy to communicate that and very often, I didn’t have to say anything anyway, because it was either as I expected or better.

Ulrike Schwarz - Courtesy of John Abbott

JA: Especially the last piece, Kverndokk’s Symphonic Dances, that we did. That was the Grammy nominee from 2018, I think…

US: 2020.

JA: Sorry. When was the last year?

US: That was, I mean, the Grammys; the ceremony was 2020, January 2020. But isn’t it a nominee from 2019 then?

JA: Well, I guess, yeah, you know, the last couple years, you can just kind of throw away. (laughs)

But the thing about that was [that] we said, okay, this music, we want to have it be much more cinematic; much more like a film score. The immersive [surround sound] element of that recording is not the orchestra on the stage, [but] the ambience in the back. It really wraps around, and I think that’s why it became a Grammy nominee. We very successfully took an orchestra and made [it] a very immersive experience.

US: About other styles. When you work for big broadcast networks, as I did, then you end up doing [many types of music]. I did a project with The Keith Emerson Band and [an] orchestra, which was kind of interesting, because we were known [in] a classical environment, and some Norwegian conductor brought in Keith Emerson and the band to Munich and Los Angeles. It was a big, let’s say, crossover, one of the biggest crossover projects I’ve done. I can’t say it was entirely successful because the ideas of how to produce something were too different. I think the outcome was, quite okay.

I’ve done Indonesian gamelan music; I’ve even done stone xylophones. Fado (Portuguese traditional music) with Mariza (Mariza – Live at Philharmonie im Gasteig in Munich). This was from a radio broadcast at Bavarian Radio, Channel 2. Most of Ulrike’s recordings were for BR Klassik. BR 2 is something different.

And Parisienne – I like Zaz very much. That was one of the best ones: Z-A-Z (French singer-songwriter Isabelle Geffroy, aka Zaz). She is great. (Zaz Live Tour – Sans Tsu Tsou, released in 2011, was from a live broadcast at Studio 2 on Bavarian Radio for a show called “Bayern 2 Studio Club.”)

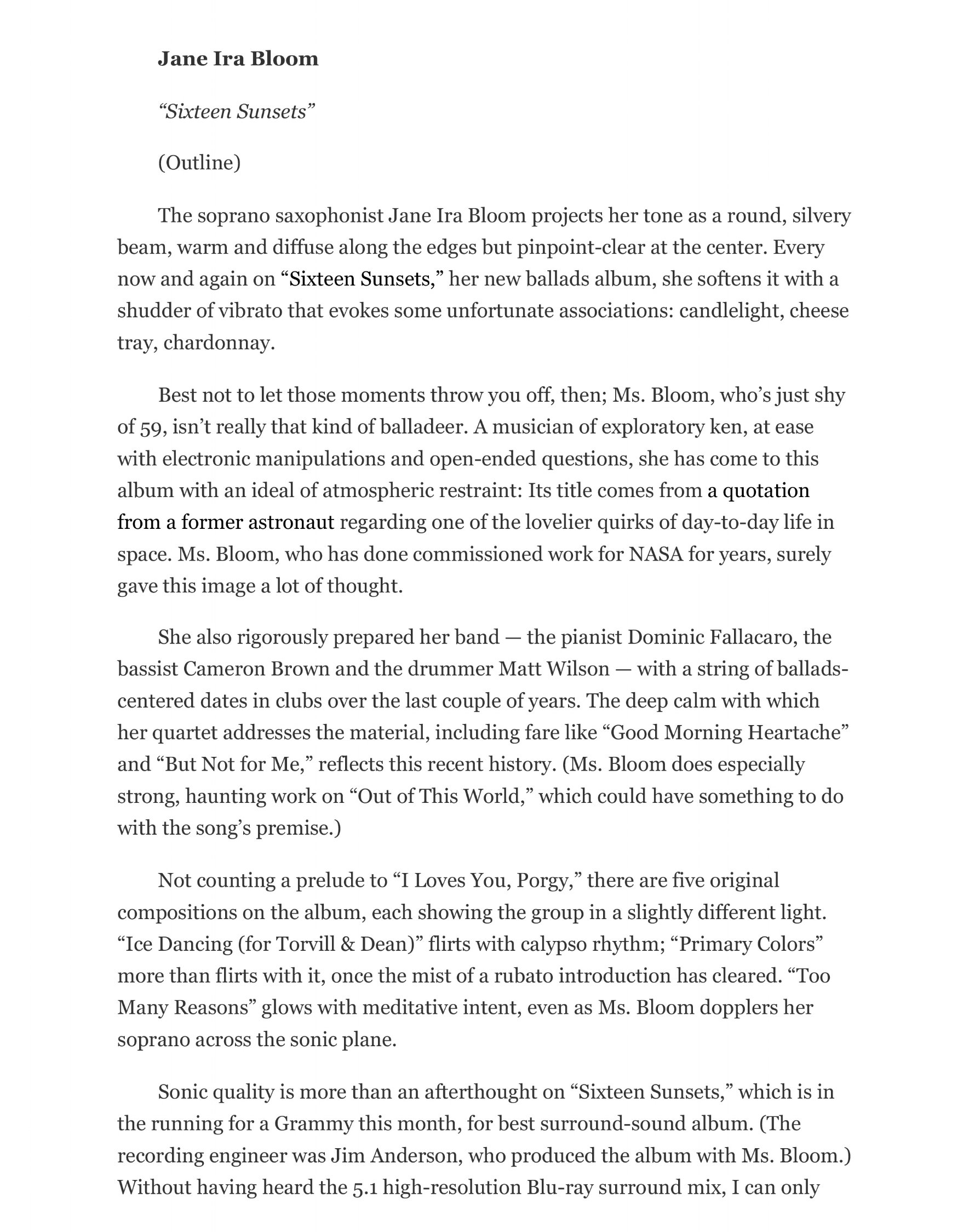

JA: John, I have a whole background in [doing] radio documentaries to add to that. When I worked with [soprano saxophonist] Jane Ira Bloom and her Emily Dickinson project (Wild Lines: Improvising Emily Dickinson), basically, she gave me the poetry that was read, and the music, and said, “you know, do your NPR thing and turn it. So, essentially, we turned it into a two-record set. One CD has the music and the other CD has the kind of NPR-type produced audio experience with poetry and music and it’s all timed out. That’s kind of where I started actually doing that kind of work and I still enjoy doing it every once in a while.

US: We have two audiobooks lined up where we want to actually, in part, do the readings and the music to them. Those will be coming out in the next two years, I think.

JS: When you’re dealing with unfamiliar instruments – say you were doing Japanese music, and you may have to record koto and shakuhachi, for example: do you have a standard fallback protocol? In order to be able to capture unfamiliar sounds, what would your favorite mics would be – those you are most familiar with?

JA: We recently did an album with Min Xiao-Fen called White Lotus. I’ve done Chinese instruments for many, many years. And I’ve always had a fascination with trying to make these instruments [which] are really foreign to, let’s say Western ears or American ears, and trying to make them so that they’re pleasing to listen to from our aspect. Trying to actually make them very high-resolution audio, and very hi-fi, because they have fascinating sounds, and they have a lot of detail that you can bring out.

Ulrike was – I like to call her my “technical producer” on that kind of thing. I was doing the recording and the mixing, but she was really maintaining our technical quality as we record.

[For a project like this], we would rely on good-quality tube microphones like the Brauner VM-1, or work with a lot of omnidirectional microphones like the DPA 4007 or 4006. We would also use Sennheiser [MKH] 8020s, and the Neumann KM 130, and all that kind of thing.

And, worrying about and really trying to create space, through spacing of microphones, doing a lot of stereo [recording], not just panned mono. With that stereo [recording], you can actually get a lot of detail that you wouldn’t necessarily get if you just put a single microphone out there. White Lotus is really a stunning recording.

US: It starts with getting out the books and reading about these instruments. When I was in Japan and asked my host there what certain instruments were, the next day I got 15 pages [from her] on the shakuhachi and the shamisen and all these things.

There is a very good book that we always go back to. It’s a German thing from Professor Meyer – What is it called again?

JA: Something that was done early on: Acoustics and The Performance of Music [1971] by Jürgen Meyer.

These days, computer simulations make everything easier, but he studied the frequency ranges of all these instruments [at various locations from the instruments]. Three-dimensional readouts of how an instrument sounds, and things like whether it might actually be useful to place a microphone sometimes even behind it, because that’s a frequency range that maybe you’d want, or don’t, or something like that.

A couple of times, [recording] with Toshiko-san (Toshiko Akiyoshi), we had three taiko drummers and a big band, and when Lew (Tabackin) played the flute, very often was trying to imitate a shakuhachi. And so, kind of knowing what that should sound like, and then being able to interpret that sound and then incorporate that into big band…

I also spent time in Japan and worked on some film soundtracks, working with the Japanese with koto ensembles [and other musicians and groups] they call Living National Treasures. All of this ends up entering [our] collective knowledge. And I can kind of know that either [something] worked or didn’t work. And I can then use the technique [that worked].

JS: Both of you are working in very high-resolution digital and specializing in immersive mixing. Since you both have long-enough track records to remember it, do you miss analog tape at all? And, are there any projects that either of you have worked on in analog that you wouldn’t mind revisiting to try to do as an immersive digital audio remix?

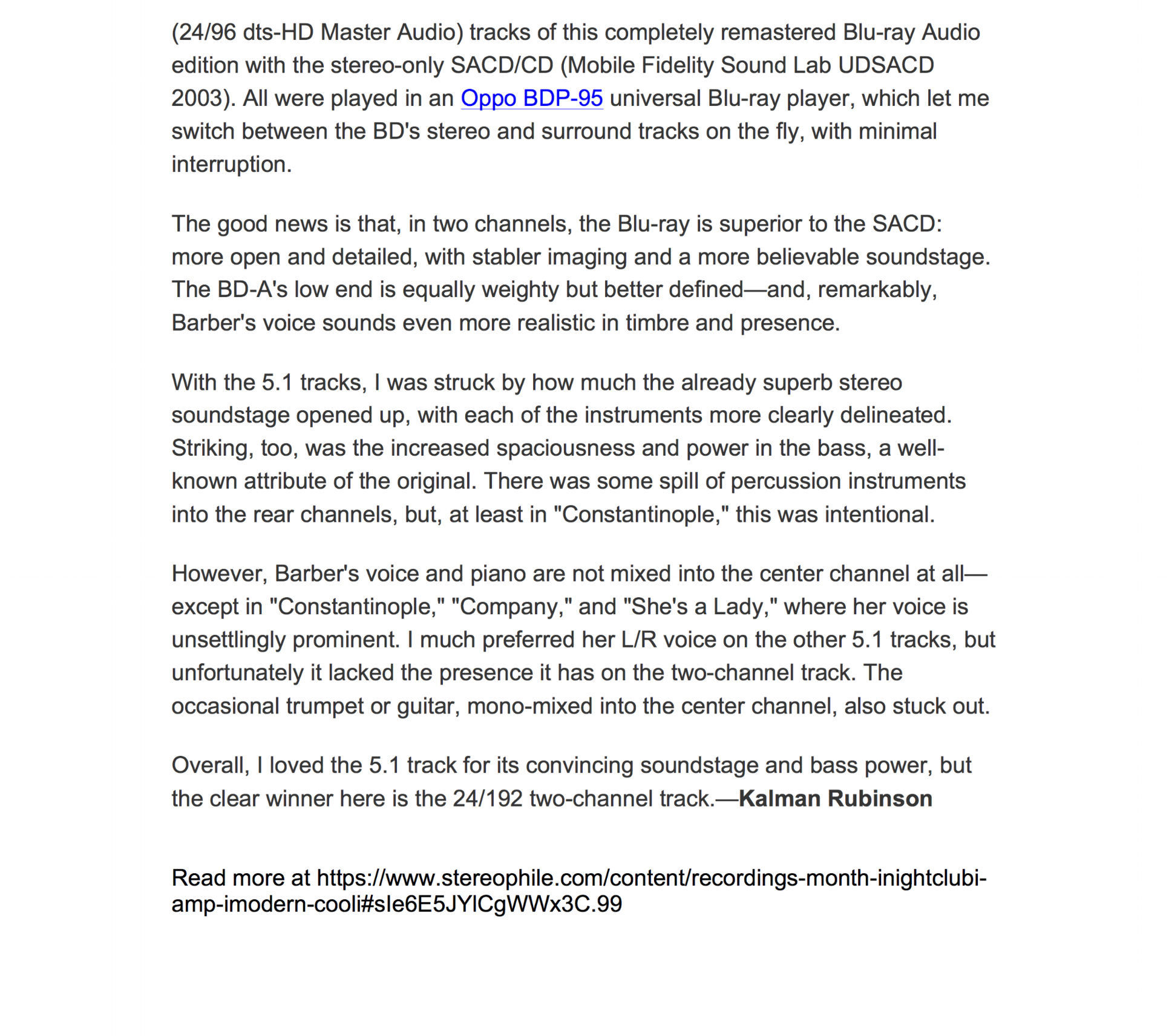

JA: (laughs) It’s not particularly the analog tape that is going to make it into an immersive recording. When I remixed Patricia Barber’s Modern Cool in 2012 or 2013 and turned that into an immersive recording, that was a recording from 1998. I had printed [recorded] two sets of microphones that I knew I could use in various formats. I essentially had enough material on tape that I could actually kind of bend and stretch and create a surround [sound environment] for immersive impression. And a lot of that comes from [the] microphones [originally used], seeing either [their] different spectral responses, or the differences in the time arrival of the sound because the mics are in different locations. And that’s really what makes [the surround mix] feel like it’s a natural environment that you’re sitting in.

As far as reverting [to analog] tape… You know, I don’t know if I really want to go back there. First off, wherever do you find the tape?

US: And the technician who can maintain it?

JA: The last recording I recorded on analog tape was back in about 2001, Terence Blanchard’s Let’s Get Lost. It was mixed and mastered to DSD by Mark Wilder and released on SACD on Columbia Masterworks. . We worked in two different studios. And the first time we did a playback, before the musicians entered the room, I hit play, and the speed was all over the place. It was just a mess. I actually had the maintenance guy come up, and I said, “get this machine out of here, get in another machine. And let’s do it again.” So, I talked to the musicians and said, “hey, we have a little problem over here; we’re gonna have to reset our machine, and we’ll have to do a new take.”

Then we had to go to another studio, [and] we had kind of the same band, but different vocalists. I’m not naming names here. But the thing was, we did a take, and before the musicians came in, we hit play. And guess what? That analog machine again was a mess – the speed was all over the place. I mean, you couldn’t play it back. The musicians would [have] looked at you and asked, “what is wrong here?” Again, we had to throw that machine out and start [over]. That was the last time I used an analog tape machine.

At the same time [this was happening], we were moving on, getting more and more into 48 channels of digital [recording] and all that kind of thing. At that time, Pro Tools really was just a toy, and hadn’t stepped up to the game yet. So, we were using a Sony 48-track for the most part back in the early 2000s. But as Pro Tools got better, we got 192 kHz [resolution] and all that kind of stuff, [and] it just became ubiquitous. Also, at that point, you couldn’t even get tape, and the [analog tape] machines became boat anchors. So everything kind of flipped over.

The one thing that has really sold us [on digital recording] is improving the sampling rate, and the sampling frequency. And improvements in clocking. I think we’ve [now] gotten results that, frankly, are better than what you could get on analog tape these days. A good high-resolution file is really hard to beat as far as we’re concerned.

Jim Anderson

US: Well, I think what is interesting in analog is, from a production point, is that in analog, you have to make decisions. The problem about digital is sometimes people can’t make decisions anymore, because track count isn’t really a thing anymore. And the hard drives are so big that everybody thinks they can do 5,000 takes, and that doesn’t necessarily get better [results]. So, there are some production aspects of [using] tape that I kind of like in that you actually have to rehearse. And then you have to make decisions. So that’s good.

On the other hand, a lot of all of what we do these days with, you know, flying in a vocal here, doing a little thing there…that would not be possible, if you happen to like the standard of what people are [now] used to, which is a good and a bad thing of perfection. It’s simply not possible in analog unless you have unlimited funds, your own technicians, and really good tape machines. And those things rarely come together.

We had recently a discussion about [using] 16 tracks, with no noise [reduction]. I mean, that is really a great sound if it’s transferred well. I did a transfer of 16 tracks last April. But we had to fly to Skywalker Sound to do this transfer, because there are just so few people around that still have machines on that level and the maintenance on that level so that you can actually do these kinds of transfers. They took care of the analog side. I took care of the digital side and I think it was a fantastic transfer.

But in terms of revisiting, I mean, we just actually did a remix of an analog thing…

JA: …but from 1992.

US: But the [original analog recording] had been transferred at 24/96 [24-bit/96 kHz], and not really with special care, which I understand, because they didn’t have the budget for it. So, it is what it is, I think, you know? (laughs)

JA: [When] I think of the analog format, I think 16-track, 2-inch [tape] at 15 ips was probably about as good as it was going to get. There’s a 1997 analog recording I did with Cassandra Wilson, Jacky Terrasson and Mino Cinelu (Rendezvous). I just got a copy of the Japanese release, and it just sounds great. Bob Belden was the producer on that. He said, “I want you to do 16 tracks.” and I asked, “Why?” He said, “so we limit our decisions here.”

So, we couldn’t load it up with a lot of vocals, and we couldn’t load it up with a lot of percussion. By the time we did a pass, we basically filled up 16 tracks at one time. It made for a very nice, spontaneous recording. But also – [having only] 16 tracks, my god.

There’s a recording I did in 1998 on Blue Note with Tim Hagans and Marcus Printup on trumpet called Hubsongs: The Music of Freddie Hubbard, and Freddie Hubbard was in the control room producing, along with Bob Belden. When I compare that album to other recordings I made during that time, it just sounds bigger and fatter than anything else from that period. And that really is because of the 2-inch 16 track analog tape format and again, at the time, there was nothing that could beat it, but now, a good high-resolution file really can compete.

Because, if I wanted to go back and do something [on analog], again, it would be to do it in that mode. I really wouldn’t go to do a 24-track analog. You know, I heard something on the radio yesterday, Ron Carter – The Golden Striker album, and when I was listening to it, I thought, “gee, that sounds pretty good.” And then I thought back, “Oh my god, that’s the one I did on 16 tracks, 15 ips with Dolby SR!”

Link: Copper Magazine - Part 2

THE COPPER INTERVIEW

Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz: Immersive Audio’s Power Couple, Part Three

Written by John Seetoo

With multiple Grammy Award wins and nominations to their credit, as well as European awards such as the Echo Klassik and Le Diamant d’Opera, Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz have a unique personal and professional partnership that has resulted in a wide range of critically-acclaimed, co-produced and co-engineered recordings. Currently, the duo is up for a 2021 Best Immersive Recording Grammy nomination for jazz artist Patricia Barber’s Clique (reviewed by Tom Gibbs in Issue 144). Part One of our interview in Issue 156 included their thoughts on making their mixing techniques as “invisible” as possible, in working with live orchestras and big bands, and discussed their favorite recordings done by each other. Part Two (Issue 157) delved into their earlier work using analog tape, their approaches towards recording unfamiliar instruments and different types of ethnic and regional music, and their transition into digital recording.

Ulrike Schwarz: At this point, I’m regretting that I gave away my Studer A-80 16-track two-inch [analog] machine when I moved to the United States. I’m sure we can find it, though. I know who has it.

But otherwise, I think high-resolution digital is the thing. It’s very stable.

Jim Anderson: The other thing is, we probably couldn’t have done the recordings we’ve done [with the [Stavanger Symphony Orchestra] in Norway, in analog. I mean, the fact that we could actually walk in there with [just] a computer and an interface…if we had to walk in there with a two-inch tape machine and tape – that would have been just impossible. Digital has allowed a lot more portability.

Kverndokk’s “Symphonic Dances” https://youtu.be/VaIymaR8wPU

US: Also, immersive audio recording wouldn’t be possible, because our main microphones – we had 13, [plus] we had about 60 additional microphones on stage and all of them were used. You can’t do that with 16 tracks.

John Seetoo: Which artists, living or dead, do you wish you had the opportunity to work with, and why?

US: Leonard Bernstein. Bernstein, but unfortunately, he’s very dead.

JA: We have friends that worked with Bernstein and the stories that are told…even the fellow in the control room having to order lunch was quite a trip. [Engineer] Don Puluse talked about when he was recording the Bernstein Mass and mixing it.

Link to Qobuz: https://open.qobuz.com/album/mapvxh6hcz2mb

Bernstein would order at the 21 Club [the restaurant] and they would bring over lunch on a cart, because Columbia [Records] was around the corner. The story that they don’t tell – well, I think we’re allowed to tell this now, but when the bill came, he didn’t know what to do because he wasn’t used to picking up the bill. (laughs)

In the jazz world, you know who I would love to have worked with? Henry Mancini. My friend Al Schmitt worked with him for years and so I was able to talk to Al about Mr. Mancini. Also, Mr. Mancini is from my area of Pennsylvania, so I grew up following his career. Ulrike’s probably tired of it, but every once in a while, I will pull out a Mancini record and just put it on the record player. Working in Hollywood, on sound stages, recording any of those scores that he did for film – that would have been something I would have liked to have done.

Link to Qobuz: https://open.qobuz.com/album/0886445007404

US: Mr. Bernstein spent most of the ’80s, actually, in Europe, and a lot of time with the Bavarian Radio Symphony. And of course, my colleagues, the older colleagues from radio, had all these stories about their Bernstein recordings and traveling with Bernstein and all these things, and just actually sitting there listening to him in rehearsals, which he’d done for more than over a decade. You learn so much about music, and how these conductors really are. And you’re getting paid for it. Every week was with a major conductor.

Somebody that I would also love to work with, and whom I only had once the opportunity to see in concert – because she usually cancels when I have tickets – is [pianist] Martha Argerich. Of course, I mean, she’s like one of the holy, holy saints to me.

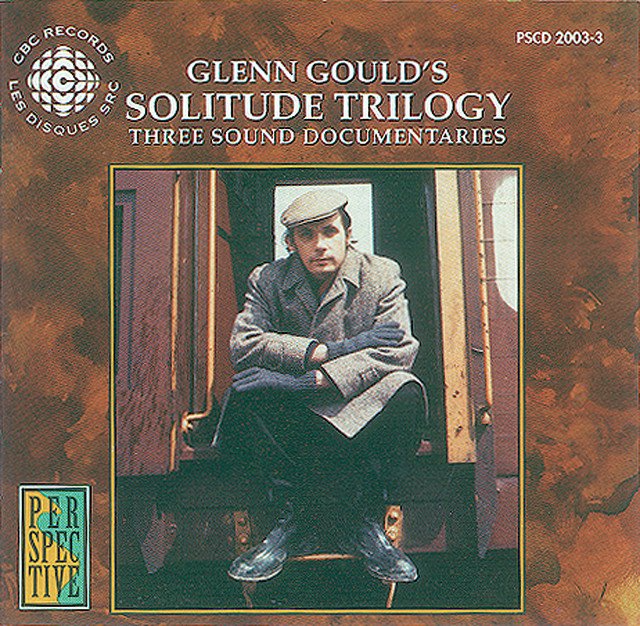

JA: Another person I find fascinating in every aspect is Glenn Gould, both in his solo piano recordings, but also on his radio documentaries for CBC [the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation], The Idea of North and all that kind of thing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tsux27kMwjc

I teach a podcasting class at NYU, and I get the kids to actually listen to Glenn Gould’s radio documentaries. I’m sure he was impossible, his demands and the working methods, but I think the result…

JS: Would you have put his humming on a separate track?

JA: (laughs) The thing is, you don’t have a choice. It’s everywhere, it’s ubiquitous, it’s on every… you know, you just can’t do anything about that.

US: And it’s a very good way to keep people from editing!

JA: Like Gould, Billy Taylor also hummed along when he played and he would try to have us not get his humming in a recording. People work differently when it comes to that kind of thing. I know what you mean by Gould, but if it’s a natural noise [like someone humming], that doesn’t bother me. If it’s an electrical noise, that’s when my ear perks up.

Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz at Skywalker Sound.

JS: What has been your biggest challenge in mixing for immersive audio? In a past interview you mentioned a client that expected elements to magically show up in your mixes, even though they were never actually recorded! Have your Grammy-award-winning reputations in the immersive area magnified these kinds of unrealistic expectations?

US: I think the biggest part is when somebody comes to us and says, “we would like to try for a Grammy nomination…” and this does happen (laughs). I think managing the expectations from the start is one of the most important aspects.

For example, Stavanger [Gisle Kverndokk’s Symphonic Dances, recorded by the Stavanger Symphony Orchestra] was a case like that. And we made it very clear that you can’t [expect a Grammy] on the first…First of all, we can’t go here. Second, not the first time out. The [artist] has to build up a name. And if the music isn’t happening, then it will not get recognized. [Symphonic Dances eventually did garner a Grammy nomination for Best Immersive Audio Album – Ed.]

JA: I think another aspect of what Ulrike is saying is: when you blow this music up into immersive [sound] and it’s coming out of X amount of speakers, the music itself has to be really good, because the bigger you make it, if the music is lame, it just sounds big and lame. So, you really have to have a great musical performance to really put this thing across.

US: In classical music it’s actually more difficult to edit in immersive, because a lot of things you can hide in stereo, and it gets a little more difficult in 5.1. Also, in immersive audio, you have to be really very sure about your edits, so the performance has to be even better, because the editing possibilities are smaller.

Ulrike Schwarz at work.

JA: In immersive, especially in classical music, you can hear these very subtle changes in the “air.” So, you can’t just go plugging in note after note after note. You really have to have a great performance that doesn’t need a lot of surgery applied to it.

JS: You’ve both been working in immersive audio for a long time, and seen its growing pains and development up to its present state of the art. During that time, what breakthroughs along the way made you go, “wow, that sounds wonderful! That’s going to be something I’ll be able to use for the next 20 years.” Or on the other hand where you thought, “I don’t think that’s going to stand the test of time.”

For example, did you think that the dummy heads historically used for binaural (stereo) recording, would now be coming back into use? (Binaural recording involves using two microphones, often with a literal dummy head with microphones placed at its ears. It can be extremely effective in creating the illusion of “3-D” stereo sound and being in the room with the performers.)

JA: The dummy head recording, true binaural recording, is really very effective, especially if you listen to the playback on headphones. [If] you listen to a recording on speakers, not so much. But, if you take the dummy head and put it in the proper placement, [you will hear] a very effective playback. Things have gotten better. A good two-channel binaural recording can be a very effective way of listening to music.

The Neumann KU 100 is actually an excellent microphone system.

US: It costs over $10,000. And we’ve been in two auctions last year trying to actually get one and the prices were outrageous. We didn’t get it, ’cause it was too expensive. So, there you go. We would have loved to have one of them.

Neumann KU 100 microphone and dummy head system.

JA: I did an immersive mix back in, I think, ’98 – and I’m happy it didn’t come out, because it was my first [one]. The reason it didn’t come out was that at the time we didn’t have a format to distribute it. There was no Blu-ray, SACD, 5.1 distribution, [or] any kind of file downloading or anything like that. And so, I got to make some mistakes early, early on that nobody ever got to hear, so I’m very happy for that.

In fact, one of the first things I did in around 2003 was for the FIM [First Impression Music] label. They wanted to record in stereo but also wanted to start working on a 5.1 [mix] and I was trying to figure out a way, as we only had eight channels for recording at the time, using the [Sony] Sonoma system.

Link to AllMusic information: https://www.allmusic.com/album/autumn-yearning-fantasia-mw0000322688

I talked to [mastering engineer] Paul Stubblebine. And I said, “you know, if I get you a good left and right [channel], and then if I print stems [a grouped collection of audio sources, such as a drum track – Ed.], or elements that could be put into the center channel and put into the rear, from that mix – would you mind if we did that? Kind of combining in 5.1 at that time?” I was trying to get a good anchor of a left and right [channel mix]. And then, okay, how can we now fill this out? That’s sort of how I came to work in surround originally.

We presented that at the 2003 Audio Engineering Society (AES) Conference in Banff.

Paul was there. We showed our recording with a huge stereo and surround [system]. It was almost like a 1959 stereo demonstration, but we were going not from mono to stereo, but from stereo to 5.1. So, that was kind of a way to start. And then we kind of kept working at it. We graduated from 5.1 to 7.1 to 11.1. And now we’ve been doing mapping into Dolby Atmos. We’ve been finding that to be a successful way to work.

US: My genesis is a little different, because when I started at Bavarian Radio, they were already doing 5.1. So, orchestral recordings and orchestral broadcasts were in stereo and 5.1. They sent me to Japan to learn from the Japanese NHK people, who were far advanced in that, because they were already doing 5.1 all the time, and in 2006 had already developed what is now their standard of 22.2 three-dimensional recording.

In 2006, that was the first time it was presented to me, and that just blew me away, because it came with 8K video. It was just, it was just amazing. And I was able to learn from them. So, I think from 2006 on, I was doing 5.1.

In 2010, we were invited to go to the upcoming [AES] Spatial Audio conference, the successor of the 2003 Banff conference.

Three weeks before that I did my first 9.1 recording with Simon Rattle conducting a Schumann oratorio. And I could track it in 9.1, but of course, I could never mix [it] in Germany or at Bavarian Radio; I couldn’t play it back. So, I flew to Tokyo to mix it there to present it a few days later in Tokyo. The fascinating thing that I experienced [in] going from 5.1 to 3-D was that the [sonic] transparency was even better, and you could make things “float.” At that moment, I didn’t know what I was doing. But somehow, I had placed my height [channel] microphones near the choir. And so, all of a sudden, I had this third dimension where the choir started to go up in height. I had the orchestra and the soloist, and then the choir was just floating on top of it. It was an effect that I hadn’t counted on, but I really loved. All of that came very, very early. And so, developing this to what it is now has been just some fun, but we’ve [also] done it for a rather long time.

Ulrike noted: The recording was Robert Schumann, Das Paradies und die Peri, performed by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Choir (Symphonieorchester und Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks). The recording and stereo and 5.1 broadcast took place in September 2010.

Sir Simon Rattle was the conductor. The soloists were: alto Magdalena Kožená (Angel), sopranos Sally Matthews (Peri) and Kate Royal (Maiden), tenors Topi Lehtipuu (narrator) and Andrew Staples, and baritone David Wilson-Johnson. The immersive version was a 5.1.4 recording that I mixed at Nippon Hoso Kyokai (NHK) Research and Development Laboratories in Tokyo in October 2010. The recording was presented at the 40th AES Conference for Spatial Audio October 8 – 10, 2010 in Tokyo.

Sir Simon Rattle was, at the [time] of the recording, chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and with the label EMI exclusively. It wasn’t possible to release this as a CD. Now that Sir Simon has been appointed chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, the hopes to release this recording on the BR-Klassik label are high.)

JS: This question is for the Copper audiophile audience. Do you share, or do you have separate reference personal music listening systems at home? What do the components consist of?

JA: Ulrike always likes to say: “In this household, we have at least five subwoofers.” We’re sitting in the dining room right now, and we’re surrounded with a 5.1 system [where] we can listen to CDs, and SACDs and Blu-rays in 5.1. It’s a Marantz SR 6014 multi-channel amplifier with Eclipse main speakers plus an Eclipse TD725SW MKII subwoofer and a Sony UBP-X700 multiplayer. In the living room is a system I’ve had for a very long time, which [includes the] Wilson WATT/Puppy speakers and subwoofer with a Mark Levinson amp and preamp – the No. 23/25 combination or something like that. Plus, a Linn LP12 [turntable].

And there’s an Oppo UDP-205 [Blu-ray player] down here. Upstairs is where the TV is, [with] an Oppo UDP-203 [Blu-ray player and a] Yamaha Atmos soundbar with a subwoofer. Ulrike’s mastering room has Wilson CUB loudspeakers…

US: …Assisted by an Eclipse TD725SW MKII subwoofer, and I have Benchmark AHB2 monoblocks with the HPA-4 preamp and, well, my DAW [digital audio workstation]. While I have [an] iFi Diablo [DAC], usually I work with Merging [Technologies pro audio hardware].

Benchmark HPA4 headphone/line preamplifier.

JA: Since the pandemic started, we haven’t had a living room, so the Wilson system also sits next to our mixing system, a stereo mixing system which has Meyer HD1 [monitor speakers], and then with the Merging system I have…

US: …A little Millennia mixing board…

JA: …Plus the Avid S1 mixing system – a couple of those, so I have faders I can actually mix on.

And then, we have the Capitol Chambers [Universal Audio software plug-in version of Capitol Studios’ famous echo chambers] available to us, which is really quite wonderful. So, we can [do] mixing here. In fact, we actually mixed White Lotus with Min Xiao-Fen in the living room. It’s also recorded in super-high-resolution. And frankly, to me, it’s every bit as good as anything I’ve ever been able to turn out of a New York studio, which is enlightening and depressing at the same time, because I love working in New York studios.

US: We actually went a little wild – we have all custom-made cables; all AccuSound cables. We installed power [conditioners] and exchanged [the stock power] cables…

JA: …for MusicCords from Essential Sound Products.

US: So, actually, there is less noise [in the setup] because the cables are much shorter. It’s not like they have to run through patch bays [in a recording studio] and everything. And so, it is depressingly good what you can come up with. But I also love to go out to big studios…what was the second part of the question? What if we had unlimited budgets and unlimited space at home?

We both love the B&W 802 [loudspeakers]. The old B&W 802s that they have at Skywalker [Sound], I would love to have them at home. Alternatively, the Magicos – I’ve fallen in love with those. Wouldn’t those sound nice in Brooklyn?

JA: I think it’s the S5. [Currently the Magico S5 Mk II – Ed.]

Magico S5 Mk II loudspeakers.

US: We like those a lot. If we could stack them with the Merging Technologies clock [the MERGING+CLOCK] and their whole MERGING+PLAYER system, that will be another nice addition in terms of, you know, getting their “super clock,” which, in the meantime, we have purchased..

I was in the market for tube amps from McIntosh, but I needed them for work. So that’s why I went to the Benchmark [amplifiers], because the [amps I needed] had to be super precise. The McIntosh didn’t give me what I needed there.

Benchmark AHB2 power amplifier.

JA: Yeah, it’s funny in that what we require professionally is different from what we require for listening as audiophiles.

JS: Don’t you need flat response when you’re working?

JA: Well, yes, flat and accurate and precise and very, very fast. We found the McIntosh amps to be very nice, but also a little bit slow and very forgiving and, frankly, we don’t need that. We need to hear something that’s…

US: …That’s giving it up to us straight, you know?

JA: We need something that’s gonna tell us [a recording] is not very good. That’s one reason why I like the Meyer HD1s there; they are not “musical” speakers.

I always find myself saying, if I can work with the HD-1’s and get the mix to the point where I can tolerate it, then it’s going to be a pretty good mix. That then will translate [with] just about any work.

We discovered the B & W 802s during the last three or four projects with Patricia Barber while mixing at Skywalker. And I’ve really come to like those a lot. At Skywalker, you’re [there] for a long time, 12 hours a day at a minimum. And I find the 802’s not to be fatiguing; they’re very, very easy to listen to for a very long period of time.

US: Our main mixing setup at home in Brooklyn is based on Merging Technologies components from their professional line. For mixing, we use an MT Horus AD/DA interface that is connected via LAN to the computer with MT Pyramix software. This enables us to work in resolutions like DXD, 384 kHz, and/or DSD. The digital controllers are, at the moment, several Avid S1s. Stems and outboard gear (if needed) will be summed on an analog Millennia Mixing Suite and re-recorded to Pyramix.

This system can run in stereo, 5.1, or immersive (meaning 3D audio, 5.1.4, 7.1.4, and up to 22.2 formats). After the latest upgrade, we are also capable of creating our own Dolby Atmos files.

The speaker system in our house only allows for 7.1 playback at the moment. For more elaborate mixing and playback scenarios, we like to travel to Skywalker Sound for their excellent control room acoustics.

Link: Copper Magazine - Part 3

THE COPPER INTERVIEW

Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz: Immersive Audio’s Power Couple, Part Four

Ulrike and Jim Anderson

Written by John Seetoo

With multiple Grammy Award wins and nominations to their credit, as well as European awards such as the Echo Klassik and Le Diamant d’Opera, Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz have a unique personal and professional partnership that has resulted in a wide range of critically-acclaimed, co-produced and co-engineered recordings. Currently, the duo is up for a 2021 Best Immersive Recording Grammy nomination for jazz artist Patricia Barber’s Clique (reviewed by Tom Gibbs in Issue 144). Part One of our interview in Issue 156 included their thoughts on making their mixing techniques as “invisible” as possible, and in working with live orchestras and big bands, and discussed their favorite recordings done by each other.

Part Two (Issue 157) delved into their earlier work using analog tape, their approaches towards recording unfamiliar instruments and different types of ethnic and regional music, and their transition into digital recording. Issue 158 and Part Three explored their appreciation for Leonard Bernstein, Henry Mancini, and Glenn Gould, as well as their early histories in mixing for immersive audio; details about their home studio, which rivals many professional surround-sound establishments; and some of the differences between the equipment they choose for work as engineers as opposed to what they listen with for pleasure as audiophiles. This installment goes further into the latter topic, and concludes the series.

Ulrike Schwarz: I [listened to] McIntosh (tube amps) for 12 hours a day [for a while]. And those were very, very nice ones. I’ve heard [our recording of Patricia Barber’s Clique] on Wilsons – on the WAMMs, or whatever they’re called. I mean, it’s just kind of fun. But I do prefer the Magico [S5] – that to me, is more musical. [The latest version of the Wilson Audio WAMM is the WAMM Master Chronosonic – Ed.]

I bought a PMC 5.1 [speaker] setup (models TB2+ and TLE1) for my home because I was having trouble mixing non-classical content on the ARD (national German broadcasting network) standard speakers, the Geithain 901. There is a range between 200 to 400 Hz that is so indistinguishable on the Geithains that I felt the need to check myself at home. I also had a pair of Dynaudio BLM06 active speakers stored at Studio 2 of the Bavarian Radio studio building that I would use for jazz recordings.

Also, I like listening to our [radio] broadcasts and DVD-Audio, SACD and Blu-rays at home in 5.1.

But it kind of blends. I wouldn’t want to have too-forgiving speakers even to listen to for fun because I would be looking for things [to hear that weren’t there]. Jim was talking about Revel [speakers], and I don’t get along with the Revels.

Jim Anderson: The reason I brought those up was [that] we were using them in mastering and I found them to be actually pretty nice, but I think we found stuff we like better. So yes, if Magico wants to give us a pair, we’ll be very happy to take them. They know we’re very good at evaluating equipment.

John Seetoo: Regarding Patricia Barber: congratulations on the latest Grammy nomination (for Clique). You have quite a number of records that you’ve done together. First part of my next question: what was different about producing Clique versus, say, Barber’s Café Blue or Modern Coolor your other records? And, is there a particular methodology or chemistry that you have working with Patricia that make your collaborations so productive?

JA: Thank you. I’ve said this before in other interviews, but every time we’ve gone into the studio, I have always tried to look at, what’s the state of the art today? Every time we’ve gone in the studio, there have been changes, incremental changes.

Café Blue was done with a 16-bit [D/A] converter for me to mix with at the time, and that was the best we had. And then we stepped up when it came to Modern Cool. We started working in a higher-[resolution] format, [with] higher track counts and all that kind of thing. Every time we’ve stepped up, we’ve always addressed what [the state of the art] is at the moment.

The other thing about Café Blue was, I built a live [reverb] chamber in the stairwell. And that was the reverb that everybody kind of fell in love with at the time. An “analog” live chamber that was built with microphones and speakers – just the way you do [it] at Capitol Records [Studios], you know, you have a very live room [in which] you put in microphones and speakers, and that’s the reverb.

But when we started getting along to Patricia’s album Verse, Sony sent me a DRE-S777 [sampling digital] reverb, and I did a convolution of that stairwell. And I still have it, if I need it. So, I was able to go from setting up a live chamber to actually using a convolution of the live chamber. [Convolution reverb uses digital recordings of real spaces to apply the reverb effect – Ed.]

And then, when we got to Smash, I had just done the Modern Cool remix in surround at Skywalker [Sound]. And so [they asked], “where would you like to mix?” “Skywalker!” [Their reply was] “Sure!” We’ve [gone] out there since 2012 when we want to mix Patty. So again, that’s another way that we can move up.

When we got to the last two albums: Higher, and Clique, we started looking around, saying, “okay, how can we increase the technical aspect of the recordings?”

That’s when we got into high-resolution 352.8 kHz, and starting working in DXD [the Digital eXtreme Definition PCM format at 352.8 kHz/24-bit – Ed.]. So, we mixed Higher first, because that was coming out first. Then a year later, we went out [to Skywalker]. And we were able to, again, for this last record, use the Merging Technologies, what’s it called?

US: MERGING+CLOCK…

JA: We put [this] really excellent [digital master] clock in the system. And all of a sudden, oh, my gosh, the recording just locked together. I think that’s what makes Clique kind of really work. It’s the stability of the image.

The other thing that we did with both Higher and Clique was that we really paid attention to every aspect of electrification of all the equipment. Every AC cable was replaced with Essential Sound Products’ MusicCord. We also use the Essential Sound Products Power Distributor. We really paid attention to the power [going] to the clocking and all that kind of thing. We’ve stepped up the game every time that we’ve stepped into the studio with Patty.

US: At Skywalker we bring in, of course, the audio interface and the tracks, obviously, but also, I brought in all the patch cables and snakes that we sometimes use. We fly five bags of metal out to California.

Ulrike Schwarz

JA: At the same time, I don’t want Patty to be aware of any of this stuff. Because basically, she wants to walk into the studio at three o’clock and start recording. So, I’ll have the band come in at about one o’clock. We’ll soundcheck them, we’ll get everybody comfortable.

And then I’ll have Patty set up. She’ll come in, and she’ll just put on the headphones and see if she feels comfortable – and then go from there. What I try [to create], essentially, for her, is [that] we’re basically doing the same record ever since Café Blue up until fifteen records later. To her, it’s the same situation: That’s so she’s comfortable, she can sit down, she knows it’s gonna be a good product. And it’s really so they can just perform.

That’s always the issue. Trying not to get the tech… you know, this goes back to the first question on trying not to get the technology in the way of the performance. She can come in, sit down and then when she hears the first playback, she’ll say, “oh, that’s fine.”

And the thing is, I try to get the best sound I can on every instrument and then blend that together, so she just sits on top of the whole thing. And she’s really appreciative of the efforts that we put forward for her.

US: I think actually, Jim is underplaying this a little bit. If you’ve been with a person for 30 years, I think it’s more than just giving stability. I mean, you’re friends with her. And that, of course, makes it much, much better, much easier for her to give out, because it is a vulnerable situation for the singer and the band and everything to be there. And just to see that you have the stability and the friend on the other side – I would think is a very big part of why this [arrangement] works so well.

JS: Do either or both of you think immersive audio will catch on more commercially with a wider audience outside of the home theater and audiophile markets? Do you think that the video game sector might be the first of other potential applications for immersive audio?

JA: At the Audio Engineering Society (AES), we did a [seminar] on gaming audio 20 years ago. And they essentially were doing immersive sound [even] back then. Even on the most basic of games. I think when it comes to immersive sound, you can be a lot more creative, in just creating atmospheres and things like that. In VR, audio is usually about five years behind the visual. So, I think we’re now catching up to where VR was when we first put on Oculus glasses and said, “wow, isn’t that great? Too bad it doesn’t sound that good.”

Now it’s starting to get to the point where you really have a [true] immersive sound [in gaming and VR]. And so, I think that the play now is getting an immersive sound out of just a pair of speakers; I think it’s going to be difficult for really quite a while. Probably eventually, that’ll improve. But, are people really going to be as crazy as we are and have a room that has six speakers sitting in it? Or more?

We find with [Dolby] Atmos, [the sound from] a soundbar is actually not bad and pretty convincing. And so, I think if you can make it pretty easy for the consumer, it’s kind of a drop kick or a forward pass or whatever it would be. Make it easy for the consumer to understand how it gets set up, so they can set it up properly and it’s effective in their room architecture. I think that is what’s going to really make it work.

Jim Anderson behind the board with Ulrike Schwarz looking on.

US: I think the [potential] immersive aspect of [listening in] airports and headphones; that is something that the overwhelming amount of people will listen to. Again, the acoustic and the room thing is great. But I think what is happening with Apple immersive or whatever it’s called at the moment [Spatial Audio with support for Dolby Atmos – Ed.] is that they’re banking on all this kind of binaural 2-channel immersiveness. I think that [still] really has to develop because [a lot of it] at the moment still sounds like phased stuff in the back, and neither Atmos nor 360 really works yet, but that’s also due to the heavy data reduction. If you could take like a real immersive-channel bass mix, and then play it against the same version in Atmos, you don’t want to hear the Atmos. There’s something to be said for bandwidth. And then for getting better tools to make a – let’s say a channel-based immersive [recording] and turn that into a 2-channel version. I’m still looking for binaural audio to catch on – that is the one that will work at some point.

But, for example, coming back to the Japanese and their 22.2 system [covered in Part Three, Issue 158], they broadcast the Olympics, the Tokyo Olympics in a binaural version. And that’s the best thing I’ve ever heard in binaural, so there is a way to do this. I think with digital transmission and everything, it’s possible.

JA: We were listening to the BBC Olympics coverage. And if you listened to the atmosphere of the live broadcast coming from Tokyo, you could tell that, especially listening through headphones, that thing was a really good immersive [sonic] bed that they were working on; then putting an announcer on top of it. And so, I think it’s gonna come along. In fact, I think more and more television will be done immersively. And then, of course, iPads and computers and things like that. We’ll be sitting here and we’ll have this kind of little “immersive ball” sitting in front of us.

US: They’re doing it already.

JA: Yeah, they are doing it already. So, it will become more ubiquitous as time goes by. I think the whole thing is just starting. And it’s nice that we’re in the pioneering stage and we’ve been able to make a bit of an impact on this already.

JS: Fascinating. Jim, you’ve been president of AES, and you’ve also given presentations at Capital Audio Fest, a high-end audio consumer show. What do you feel are the differences and similarities between the pro and consumer audio equipment markets, and what do people in the pro industry and audiophiles listen for? Ulrike – your experiences as well?

JA: Well, when you talk about the Audio Engineering Society, it’s multifaceted, in that you have researchers doing serious research in audio, and then you have educators. Then you also have practitioners, people in the studios working, so you have those three streams that really come together. But it never really branched over into the audiophile [community], which is a whole other world.

I don’t know many educators who can afford to be an audiophile. I don’t know many researchers that have the time to step out of their research laboratories and become audiophiles. It used to be said [about] old recording engineers from back in the ’70s: they had a pair of Advents and a good amplifier. And that was about basically what almost every recording engineer had in their house, because if you were walking into a recording studio, [you were thinking:] “why do I need to spend a lot of money on a [home stereo] system when that’s what I do daily?” So, they would usually have something that was adequate. [Or] better than adequate, shall we say, something really good, but not embarrassing. It’s very funny, these worlds. I don’t know that they ever would really come together.

Practicing recording engineers usually never spend much time with each other, except at conventions. (laughs) That was the whole thing about the pandemic; the last couple of years, recording engineers would go into a room for 12 hours or more, and then come out…

US: …a month later…

JA: …and then, I was saying to a lot of people, “Welcome to my world, and this is what we’ve been doing for 40 years. Going into a room and never coming out, never seeing anybody.” It’s pretty solitary work. You might be spending time with the assistants and the producers, and maybe the musicians, but that’s about it. And usually, you don’t want anybody that’s not involved in the project hanging around, because it’s such concentrated work.

So as far as, let’s say, audiophiles and professional audio [people]: do they ever really get together?

Ulrike and Jim

US: No, [it] happens. But there have been no initiatives to [have everyone] come closer. [However}, I know that the boss of the VDT, the German Tonmeister Association [Verband Deutscher Tonmeister]and the people of the German high-end societies are now mutually like associate members of each other. And they’re trying to get a little bit closer together. Of course, they are professionals. When it comes to cables, for example, we had people from the IRT do measurements and [they] said, “you know, this great cable is what you need.”

And then of course, some audiophile comes in; “but if you take this cable, everything is so much better.” And the [IRT people] had to say, “yeah, well, we measured it, [but] we have to lay out five kilometers of it, and you want $1,000 per meter.” So, this is not going to happen in a professional surrounding.

(Ulrike notes: The ARD Network had a famous research institute called Institut für Rundfunktechnik (Institute for Broadcast Technology), IRT. In the same manner, Radio France has IRCAM and NHK runs NHK STRL in Japan as their own research laboratories. Unfortunately, the IRT was closed in 2021 due to lack of funding by the ARD Network.)

There are things where a broadcaster, for example – you just [have to] make it sound very good; you have to make it sound clear. There is a focus on what you have to do. And the audiophile worries about perfecting it, making it even better and even better. And sometimes, “audiophile” can turn into voodoo. In a broadcast system, you just don’t have time for that.

JA: But at the same time, Ulrike and I love going to the Munich high-end show [HIGH END Munich].We also love going to the professionals of the VDT shows and the AES conventions and things like that. We love crossing [over with] those things. At the same time, we love presenting at the high-end shows, and explaining, because not a lot of people really understand what it takes to make a recording. So, we can play a recording, explain it, and kind of clarify, because there’s a lot of, as Ulrike said, “voodoo.” There are a lot of misunderstandings about how recordings are made. Some of them are just practical. And some of them are…you don’t want to know how the sausage is made, really.

US: And the other thing between audiophiles and professionals is that some of [the products] might [use] the exact same components, but they have to look very different to a pro and to an audiophile. I mean, we usually don’t get the stainless-steel brushed exterior, but maybe the same chip.

I was taken [aback] when I was at the last VDT conference and I played the Clique album and I had my DXD file and had my cables with me and the whole thing. Somebody from a radio station tried to tell me how much BS all of that was and said, “well, if you measure blah, blah, blah, this will come out that way…” And at some point, I had to stop him and say, “do you have a recording that sounds like [what I’m playing]? Because we can talk about all of these things that are “not necessary.” But on the other hand, we notice how each time we put in another one of these power cables, and how we cleaned up the power, how we cleaned up the cables, how we did the clock: the recording got better and the noise floor just completely disappeared into nothing.” There is a peak people sometimes will not match, let’s put it that way. (laughs)

JA: Ulrike just got done cutting vinyl with [mastering engineer] Scott Hull yesterday on Clique. We’re making sure that the quality comes down to what audiophiles will hear in the long run. It’s not like some [people] think we go do a recording and then we just kind of let it go off into the ether. We really kind of try to maintain quality all through every format.

US: Every format that comes out.

JS: One last question: AES has always been big on encouraging the next generation of audio professionals, in their efforts in education and in networking. What advice would both of you give to younger people who want to work in the audio industry?

US: Oh, I thought I wanted to give it to The Professor! (laughs) So, okay, the professor says I started well! I think you have to realize that it’s a gift, like every profession, then you really have to…first of all, you have to want it, you have to work really hard. And you have to sustain it through times that are not easy. I mean, that’s kind of general advice to every young person, I would say.

JA: People that come to New York City think, “Oh, well, wouldn’t it be great to live here!” – until they live here, and then they realize it’s not as [much] fun as it is to visit. The audio industry is like that. A friend of mine used to say, “is that perhaps the lifestyle you want?” You may not; if you went to the studio, you may not see your family for days, weeks, months…Kevin Killen went off to do work with Peter Gabriel, and he was supposed to be there for a month or two, and he ended up being there for like nine months. He came back with a wonderful record, but at the same time, you have no idea what’s going to happen sometimes.

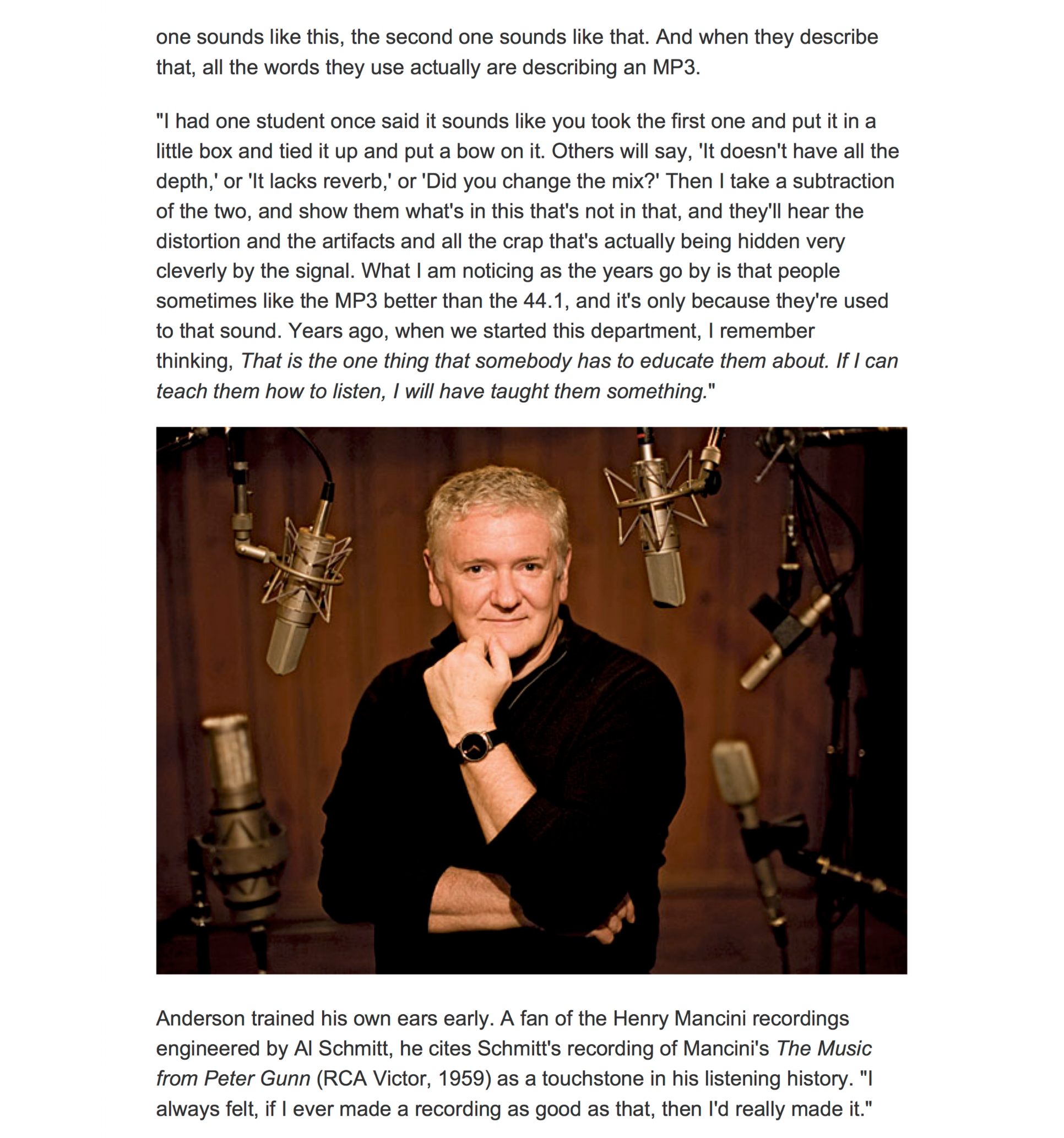

I think the most valuable education that I can offer, especially [through] my work at New York University, is my critical listening class in teaching people how to listen to a recording, so they can evaluate it. And then you can either fix it, you can improve it, you can do anything you want, but you have a vocabulary that you can [use to] talk with other professionals, and you can talk among yourselves and be very precise and very exact in what it is you’re trying to do and how you need to fix it, or how you might need to improve it, or what you’re trying to achieve.

So, I think: a good program [in how to listen]. You can learn the technique anywhere. You can go to a trade school and learn how to make a recording. But the trick, though, is musical taste. Also, history – do you understand the history of a style of recording, of jazz recording? If somebody said, “I want this to sound like a Blue Note record,” do you know how to do that? Or if you want to make it sound like a Columbia jazz record from the ’50s, do you know how to do that?

And so, you have to be a bit of a historian, you have to be a technician, you have to be an engineer. And then also at the same time, you might have to be a producer.

I mean, I know how to take apart a Steinway piano in case somebody drops a pencil in the middle of the action, which has happened at three in the morning. You have to get the screwdriver out and pull out the action and get the pencil out so you can keep recording. There are all kinds of little things that you don’t know you need to know until it actually happens to you!

US: And then there is, of course, the entrepreneurial aspect to it. I think that’s become more and more important, because the way Jim and I started was [that] we were both at these really big companies. We had a job that paid, and everything was taken care of. And these jobs are very rare at this point.

I’m very thankful that I could make all my mistakes under the big umbrella of this large company, because now, it is so much more expensive than when we would make mistakes [then], because the time probably wouldn’t come back.

So, you have to build your entrepreneurial chops as well. You have to know which direction you are going because you can’t do it all. You have to love basically the type of music that you’re doing. You have to love it. I mean, I probably would be not very good at hip-hop, because I don’t know much about it. And I haven’t listened to [it] enough to even evaluate it. So, you have to be clear on what your specialties are, then you have to also turn that, I think, into a business model, at this point. Because, again, the big jobs in studios or in big recording companies are not that frequent anymore.

JA: At NYU, we always say, “making the recording is the easy part.” It’s what you do after that. How do you get the word out that you have this recording, [and] distribute [it]? Do you know all the business aspects? Well, those are some of the most important things that somebody can learn about getting into the industry. It really is [about] relying upon yourself or your team, and being entrepreneurial.

JS: That’s fantastic advice. Thank you again for being so generous with your time and being such engaging interviewees.

Link: Copper Magazine - Part 4

Washington Square News

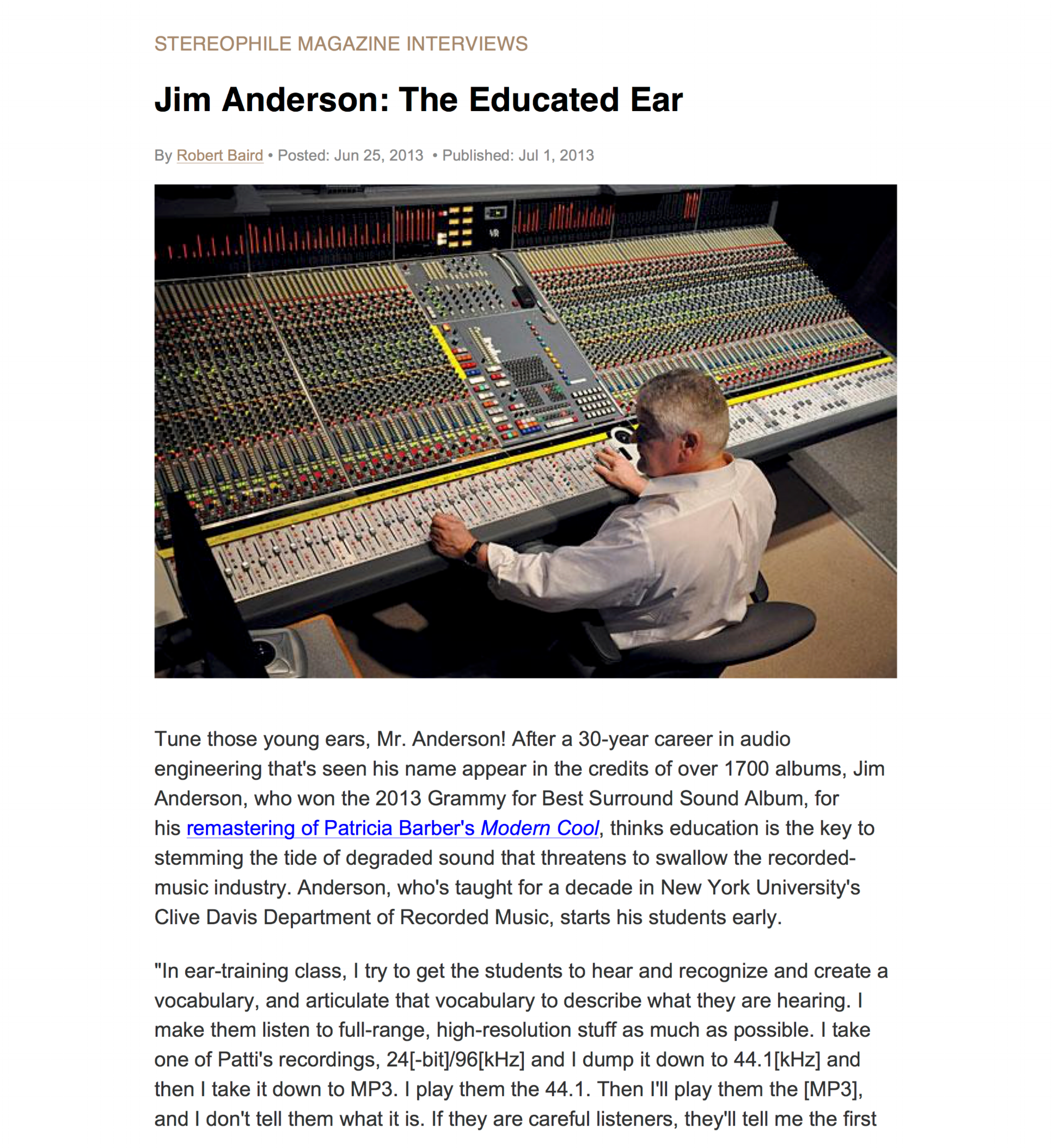

With 28 Grammy nominations, Tisch prof. Jim Anderson can’t be stopped

The recording engineer and producer maintains a busy professional life while working as a professor at the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music.

Staff Photo by Manasa Gudavalli

Founder of the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music, Jim Anderson is a 28-time Grammy and Latin Grammy nominee, with 11 of those being wins. He is currently nominated for Best Immersive Audio Album for his work on the Patricia Barber album “Clique.”

By Yas Akdag and Lillian Jones

April 1, 2022

As a college student, it’s pretty rare that you can say that your professor has been nominated for a Grammy. Now try 28. That’s how many nominations Jim Anderson has under his belt from the Grammy and Latin Grammy Awards — with 11 of those being wins.

This year, the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music professor is nominated for best immersive audio album for his work on the Patricia Barber album “Clique.” While working on the album, he and his wife, Ulrike Schwarz, were one of the first to use a new high-resolution digital audio format called Digital eXtreme Definition.

This isn’t the only time Anderson has been at the forefront of the music world — he was part of the founding faculty of Clive Davis, one of the first programs of its kind when founded in 2003. After nearly 20 years at NYU, Anderson spoke with WSN about the Grammys, his professional life and his work as a professor.

On 28 Grammy nominations

Should Anderson win on April 3, it’d be his second Grammy Award with Patricia Barber. When asked how he felt about it, he responded, “I like the idea that the work is getting recognition and it’s good enough to stand on the same platform.”

“Clique” is up against pop albums by Harry Styles and Alicia Keys, as well as some classical pieces, so Anderson isn’t 100% confident. But if you check out his track record, the odds look pretty good.